April Showers Bring ... Marine Debris to Pacific Northwest Beaches?

MAY 30, 2014 -- Over the last few weeks, emergency managers in coastal Washington and Oregon have noted an increase in the marine debris arriving on our beaches. Of particular note, numerous skiffs potentially originating from the Japan tsunami in March 2011 have washed up. Four of these boats arrived in Washington over the Memorial Day weekend alone. This seasonal arrival of marine debris—ranging from small boats and fishing floats to household cleaner bottles and sports balls—on West Coast shores seems to be lasting longer into the spring than last year. As a result, coastal managers dealing with the large volume of debris on their beaches are wondering if the end is in sight. As an oceanographer at NOAA, Amy MacFadyen has been trying to answer this question by examining how patterns of wind and currents in the North Pacific Ocean change with the seasons and what that means for marine debris showing up on Pacific Northwest beaches.

What Does the Weather Have to Do with It?

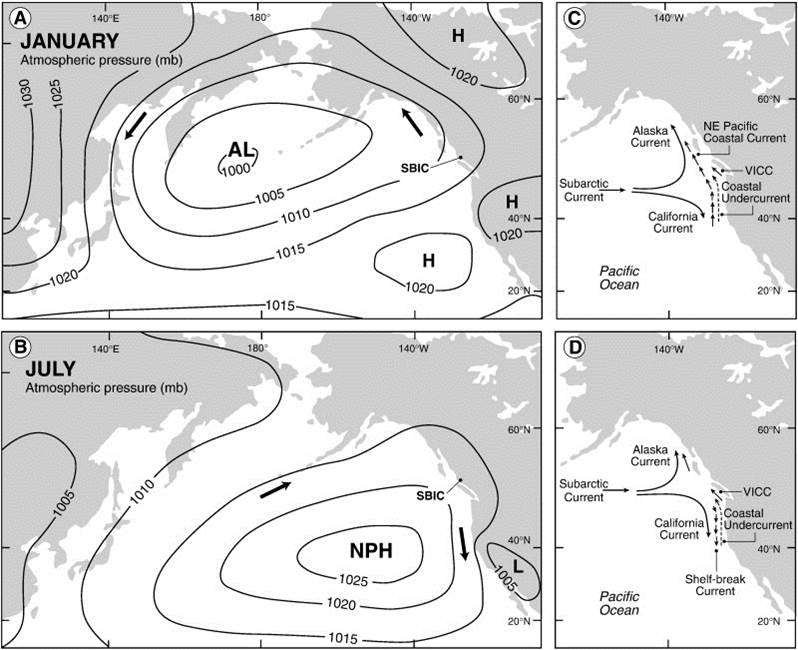

Beachcombers know the best time to find treasure on the Pacific Northwest coast is often after winter storms. Winter in this region is characterized by frequent rainfall (hence, Seattle's rainy reputation) and winds blowing up the coast from the south or southwest. These winds push water onshore and cause what oceanographers call "downwelling"—a time of lower growth and reproduction for marine life because offshore ocean waters with fewer nutrients are brought towards the coast. These conditions are also good for bringing marine debris from out in the ocean onto the beach, as was the case for this giant Japanese dock that came ashore in December 2012. These winter storms are associated with the weather phenomenon known as the "Aleutian Low," a low pressure system of air rotating counter-clockwise, which is usually located near Alaska's Aleutian Islands. In winter, the Aleutian Low intensifies and moves southward from Alaska, bringing wind and rain to the Pacific Northwest. During late spring, the Aleutian Low retreats to the northwest and becomes less intense. Around the same time, a high pressure system located off California known as the "North Pacific High" advances north up the West Coast, generating drier summer weather and winds from the northwest.

This summer change to winds coming from the northwest also brings a transition from "downwelling" to "upwelling" conditions in the ocean. Upwelling occurs when surface water near the shore is moved offshore and replaced by nutrient-rich water moving to the surface from the ocean depths, which fuels an increase in growth and reproduction of marine life. The switch from a winter downwelling state to a summer upwelling state is known as the "spring transition" and can occur anytime between March and June. Oceanographers and fisheries managers are often particularly interested in the timing of this spring transition because, in general, the earlier the transition occurs, the greater the ecosystem productivity will be that year—see what this means for Pacific Northwest salmon. As we have seen this spring, the timing may also affect the volume of marine debris reaching Pacific Northwest beaches.

Why Is More Marine Debris Washing up This Year?

NOAA has been involved in modeling the movement of marine debris generated by the March 2011 Japan tsunami for several years. We began this modeling to answer questions about when the tsunami debris would first reach the West Coast of the United States and which regions might be impacted. The various types of debris are modeled as "particles" originating in the coastal waters of Japan, which are moved under the influence of winds and ocean currents. For more details on the modeling, visit the NOAA Marine Debris website.

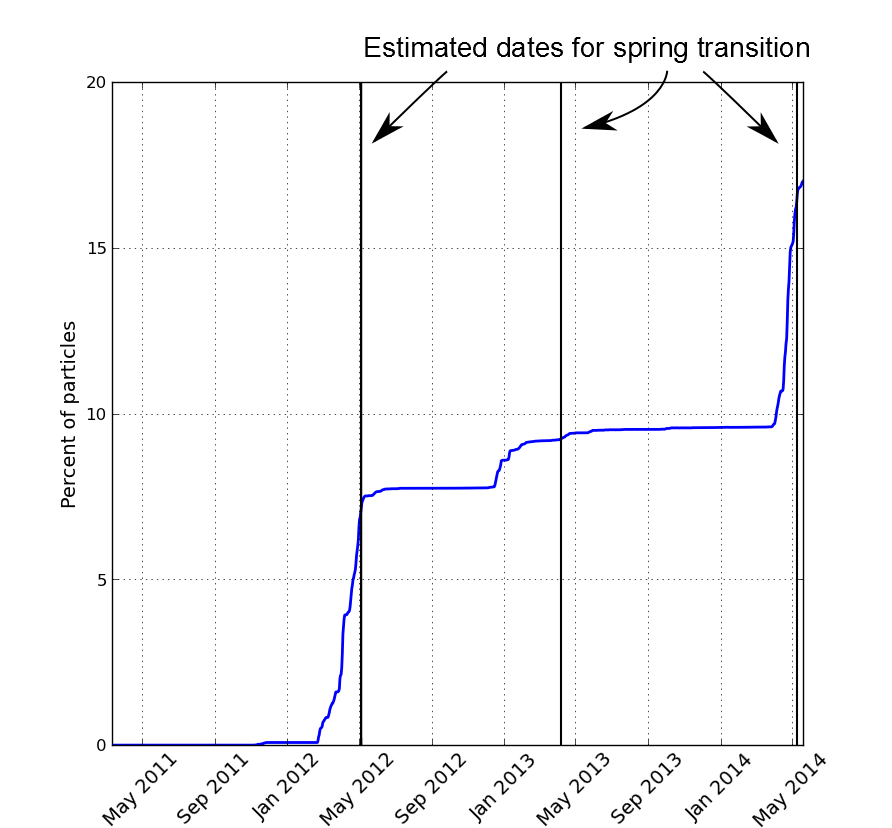

The figure here shows the percentage of particles representing Japan tsunami debris reaching the shores of Washington and Oregon over the last two years. The first of the model's particles reached this region's shores in late fall and early winter of 2011–2012. This is consistent with the first observations of tsunami debris reaching the coast, which were primarily light, buoyant objects such as large plastic floats, which "feel" the winds more than objects that float lower in the water, and hence move faster. The largest increases in model particles reaching the Pacific Northwest occur in late winter and spring (the big jumps in vertical height on the graph). After the spring transition and the switch to predominantly northwesterly winds and upwelling conditions, very few particles come ashore (where the graph flattens off). Interestingly, the model shows many fewer particles came ashore in the spring of 2013 than in the other two years. This may be related to the timing of the spring transition. According to researchers at Oregon State University, the transition to summer's upwelling conditions occurred approximately one month earlier in 2013 (early April). Their timing of the spring transition for the past three years, estimated using a time series of wind measured offshore of Newport, Oregon, is shown by the black vertical lines in the figure. The good news for coastal managers—and those of us who enjoy clean beaches—is that according to this indicator, we are finally transitioning from one of the soggiest springs on record into the upwelling season. This should soon bring a drop in the volume of marine debris on our beaches, hopefully along with some sunny skies to get out there and enjoy our beautiful Pacific Northwest coast. *Pressure system graphic originally found in: Favorite, F.A., et al., 1976. Oceanography of the subarctic Pacific region, 1960–1971. International North Pacific Fisheries Commission Bulletin 33, 1–187. Referenced in and with permission of: Galloway, J.M., et al., 2010. A high-resolution marine palynological record from the central mainland coast of British Columbia, Canada: Evidence for a mid-late Holocene dry climate interval. Marine Micropaleontology 75, 62–78.