Melting Permafrost and Camping with Muskoxen: Planning for Oil Spills on Arctic Coasts

AUGUST 6, 2015 -- Alaska's high Arctic coastline is anything but a monotonous stretch of beach.

Over the course of more than 6,500 miles, this shoreline at the top of the world shows dramatic transformations, featuring everything from peat and permafrost to rocky shores, sandy beaches, and wetlands.

It starts at the Canadian border in the east, wraps around the northernmost point in the United States, and follows the numerous inlets, bays, and peninsulas of northwest Alaska before coming to the Bering Strait.

Planning for potential oil spills along such a lengthy and varied coastline leaves a lot for NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration to consider. We have to take into account a wide variety of shorelines, habitats, and other dynamics specific to the Arctic region.

This is why NOAA Office of Response and Restoration scientists Catherine Berg and Sarah Allan, normally based in Anchorage, jumped at the opportunity to join a National Park Service–led effort supporting oil spill response planning in the state's Northwest Arctic region.

Their goal was to gain on-the-ground familiarity with its diverse shorelines, nearshore habitats, and the basics of working out there. That way, they would be better prepared to support an emergency pollution response and carry out the ensuing environmental impact assessments.

Arctic Endeavors

Many oil spill planning efforts have focused on oil drilling sites on Alaska's North Slope, especially in Prudhoe Bay and the offshore drilling areas in the Chukchi Sea. However, with increased oil exploration and a longer ice-free season in the Arctic, more ship traffic—and a heightened risk of oil spills—extends to the transit routes throughout Arctic waters.

This risk is especially apparent in the Northwest Arctic around the Bering Strait, where vessel traffic is squeezed between Alaska’s mainland and two small islands. On top of the growing risk, the Northwest Arctic coast, like much of Alaska, presents daunting logistical challenges for spill response due to its remoteness and limited infrastructure and support services.

To help get a handle on the challenges along this region's coast, Catherine Berg and Sarah Allan traveled to northwest Alaska in July 2015 and, in tag-team fashion, visited the shorelines of the Chukchi Sea in coordination with the National Park Service. Berg is the NOAA Scientific Support Coordinator for emergency response and Allan is the Regional Resource Coordinator for environmental assessment and restoration.

The National Park Service is collecting data to improve Geographic Response Strategies in the Bering Land Bridge National Preserve and the Cape Krusenstern National Monument, both flanking Kotzebue Sound in northwest Alaska. These strategies, a series of which have been developed for the Northwest Arctic, are plans meant to protect specific sensitive coastal environments from an oil spill, outlining recommendations for containment boom and other response tools.

Because we are interested in understanding the potential effects of oil on Arctic shorelines, we worked with the Park Service on this trip to collect information related to oil spill response and environmental assessment planning in northwest Alaska's Bering Land Bridge National Preserve.

The Wild Life

From the village of Kotzebue, two National Park Service scientists and Dr. Sarah Allan—along with an all-terrain vehicle (ATV), trailer, and all of their personal, camping, and scientific gear—were taken by boat to a field camp on the Espenberg River. After arriving, they could see signs of bear, wolf, and wolverine activity near where this meandering river empties into the Bering Sea. Herds of muskoxen passed near camp.

Considering most of the Northwest Arctic's shorelines are just as wild and hard-to-reach, we should expect to be set up in a similar field camp, with similarly complex planning and logistics, in order to collect environmental impact data after an oil spill. As Dr. Allan saw firsthand, things only got more complicated as weather, mechanics, shallow water, and low visibility forced us to constantly adapt our plans.

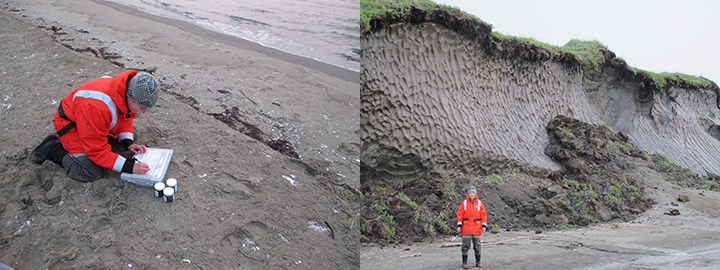

Heading west, they used ATVs to get to the mouth of the Kitluk River, where the Park Service collected data for the Geographic Response Strategies, while Dr. Allan collected sediment samples from the intertidal area for chemical analysis. These samples would serve as set of baseline comparisons should there be an oil spill in a similar area.

Traveling there, they saw dramatic signs of coastal erosion, a reminder of the many changes the Arctic is experiencing.

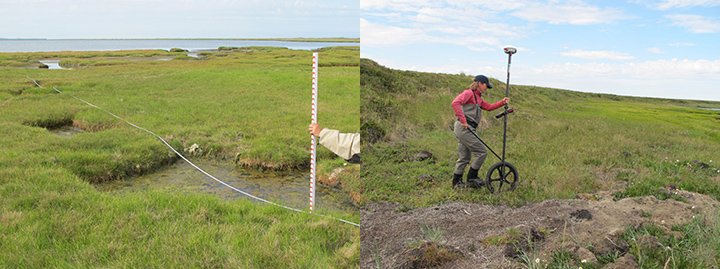

The next day, the boat took them around Espendberg Point into Kotzebue Sound to the Goodhope River estuary. There, they used a small inflatable boat with a motor to check out the different sites identified for special protection in the Geographic Response Strategy. Dr. Allan also took the opportunity to field test the "Vegetated Habitats" sampling guideline she helped develop for collecting time-sensitive data in the Arctic. Unfortunately, the very shallow coastal water presented a challenge for both their vessels; the water was only a few feet deep even three miles offshore.

After an unplanned overnight in Kotzebue (more improvising!), Dr. Allan returned to the field camp via float plane and got an amazing aerial view of the coastline. The Arctic's permafrost and tundra shorelines are unique among U.S. coastlines and will require special oil spill response, cleanup, and impact assessment considerations.

Sound Lessons

After Dr. Allan returned to the metropolitan comforts of Anchorage, her colleague Catherine Berg swapped places, joining the Northwest Arctic field team.

As the lead NOAA scientific adviser to the U.S. Coast Guard during oil spill response in Alaska, her objective was to evaluate Arctic shoreline types not previously encountered during oil spills. Using our Shoreline Cleanup Assessment Technique (SCAT) method, she targeted shorelines within Kupik Lagoon on the Chukchi Sea coast and in the Nugnugaluktuk River in Kotzebue Sound. She surveyed the profile of these shorelines and recorded other information that will inform and improve Arctic-specific protocols and considerations for surveying oiled shorelines.

Though they only saw a small part of the Northwest Arctic coastline, it was an excellent opportunity to gauge how its coastal characteristics would influence the transport and fate of spilled oil, to improve how we would survey oiled Arctic shorelines, to gather critical baseline data for this environment, and to field test our guidelines for collecting time-sensitive data after an oil spill.

One of the greatest challenges for responding to and evaluating the impacts of an Arctic oil spill is dealing with the logistics of safety, access, transportation, and personnel support. Collaborating with the Park Service and local community in Kotzebue and gaining experience in the field camp gave us invaluable insight into what we would need to do to work effectively in the event of a spill in this remote area.

First, be prepared. Then, be flexible.

Thank you to the National Park Service, especially Tahzay Jones and Paul Burger, for the opportunity to join their field team in the Bering Land Bridge National Preserve.