From Driving Underwater Scooters to Texting, Hawaii Students Learn Skills for Science Under the Sea

AUGUST 29, 2013 -- The sparkling, turquoise waters off the coast of Hawaii may seem like the perfect place to work, no matter what you're doing. But when you're trying to figure out what happened to that idyllic environment after a ship grounds on a coral reef or spills oil, those attractive waters present a surprising number of challenges. You can't just walk up with a clipboard and start taking samples. You have to haul your team and equipment out by boat, be a qualified SCUBA diver, and be able to get around underwater and communicate with your team. And this is all while (carefully and consistently) documenting the species of coral, fish, and other marine life, as well as their habitats, which might have been affected by a misdirected ship or spilled oil. To help cultivate this unique and valuable skill set in Hawaii's future scientists, NOAA has partnered with the University of Hawaii to offer a hands-on (and flippers-on) course introducing their students to a suite of marine underwater techniques. This multi-week course gives developing young scientists, all enrolled at the University of Hawaii, the critical technical skills required to succeed in the rapidly growing field of marine sciences. The course focuses on advanced underwater navigation, communication, and mapping techniques that NOAA uses in environmental assessment and restoration cases but which can be applied to almost any marine-related career.

Under the Sea

For the past month, their classroom was located in the Pacific Ocean off the south shore of the Hawaiian island Oahu. Students learned the proper techniques for using:

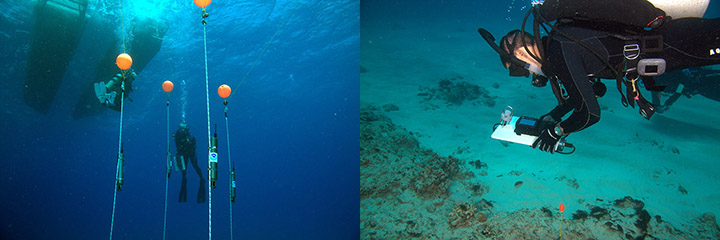

- A GPS (Global Positioning System) tracker where GPS normally can't go. Because a GPS unit doesn't work underwater, students learned how to tow one in a waterproof bag attached to a float at the surface and which is also tethered to them as they dive. The bobbing GPS unit then follows them as they take photos of what they see in the water. Later, using a program to match the photos to their locations, students can create a map of the habitats on the ocean floor.

- Underwater text messaging. While underwater, divers need a way to communicate with other dive teams when they are not in sight of each other. Instructors taught the students to use underwater communication devices that use sonar to send very basic, preset messages to others in their group or on the boat. That way, they can coordinate when someone discovers, for example, a damage site, a rare coral, or even a shipwreck. They can also use it to navigate back to the boat.

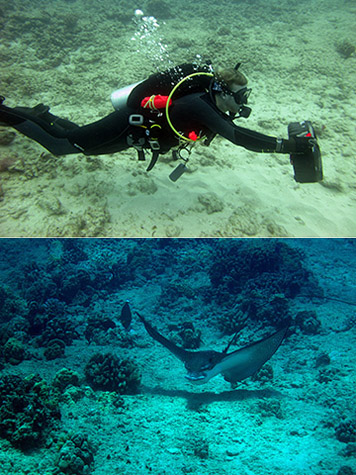

- Underwater scooters. For longer sampling surveys, students learned how to hang onto and drive a small underwater scooter. These aquatic vehicles allow divers to venture further out at a time and do so more efficiently, because they aren't exerting themselves as much and using as much of their limited air supply.

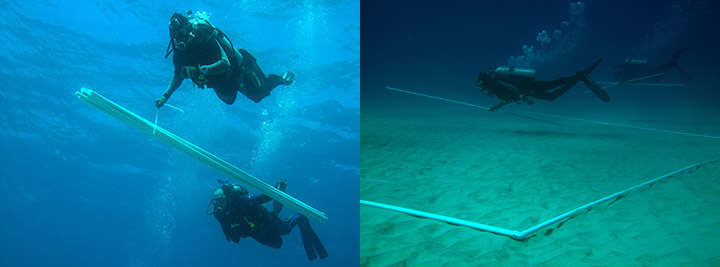

- High-precision underwater mapping equipment. This system, based on sonar, more accurately maps divers' locations in real time as they gather data underwater. Surrounded by transmitters attached to fixed float lines, students were able to enter data they collected directly into handheld devices, while also creating maps underwater.

And into Local Jobs

This year's course was taught as a partnership between the NOAA Restoration Center, the NOAA Pacific Islands Regional Office (PIRO), and the University of Hawaii Marine Option Program, with collaboration from staff with the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. The course was supported by PIRO's Marine Education and Training program.

Efforts such as this one are aimed at keeping young scientists with local ecological skills and experience in Hawaii by allowing them to advance their knowledge of practical underwater techniques. Having this specialization enables them to stay employed in the region and in the field of marine science. Ideally, local students gain the technical skills they need to work in the natural resource management field in Hawaii. After taking the marine underwater techniques course, a number of highly specialized jobs would be open to them, such as conducting:

- Environmental damage assessments after ship groundings.

- Academic research.

- Search and salvage missions.

- Mitigation surveys for underwater construction projects.

Underwater Expertise in Action

This kind of underwater expertise was called upon in 2005 when the M/V Casitas ran aground in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, in what is now the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. NOAA divers reported to the scene of the accident to help determine the damage to corals and other parts of the environment caused by the initial ship grounding and subsequent efforts to remove the ship. Using several of the techniques taught in this course, divers were able to accurately determine not only the locations where corals were injured but also how much of the reef was injured (about 18,220 square feet). This information was essential in the process of planning for restoration after the grounding. You can read more about the resulting restoration projects in an earlier update.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.