As Oil Sands Production Rises, What Should We Expect at Diluted Bitumen (Dilbit) Spills?

JUNE 20, 2014 -- NOAA environmental scientist Jessica Winter has seen a lot of firsts in the past four years. During that time, she has been investigating the environmental impacts, through the Natural Resource Damage Assessment process, of the Enbridge pipeline spill in Michigan.

In late summer of 2010, a break in an underground pipeline spilled approximately 1 million gallons of diluted bitumen into a wetland, a creek, and the Kalamazoo River.

Diluted bitumen ("dilbit") is thick, heavy crude oil from the Alberta tar sands (also known as oil sands), which is mixed with a thinner type of oil (the diluent) to allow it to flow through a pipeline.

A Whole New Experience

This was her first and NOAA's first major experience with damage assessment for a dilbit spill, and was also a first for nearly everyone working on the cleanup and damage assessment. Dilbit production and shipping is increasing. As a result, NOAA and our colleagues in the field of spill response and damage assessment are interested in learning more about dilbit:

- How does it behave when spilled into rivers or the ocean?

- What kinds of effects does it have on animals, plants, and habitats?

- Is it similar to other types of oil we're more familiar with, or does it have unique properties?

While it's just one case study, the Enbridge oil spill can help us answer some of those questions. My NOAA colleague Robert Haddad and I recently presented a scientific paper on this case study at Environment Canada's Arctic and Marine Oil Spill Program conference.

In addition, the Canadian government and oil pipeline industry researchers Witt O'Brien's, Polaris, and Western Canada Marine Response Corporation and SL Ross [PDF] have been studying dilbit behavior as background research related to several proposed dilbit pipeline projects in the United States and Canada. Those experiments, along with the Enbridge spill case study, currently make up the state of the science on dilbit behavior and ecological impacts.

How Is Diluted Bitumen Different from Other Heavy Oils?

Dilbit is in the range of other dense, heavy oils, with a density of 920 to 940 kg/m3, which is close to the density of freshwater (1,000 kg/m3). (In general when something is denser than water, it will sink. If it is less dense, it will float.)

Many experts have analyzed the behavior of heavy oils in the environment and observed that if oil sinks below the surface of the water, it becomes much harder to detect and recover. One example of how difficult this can be comes from a barge spill in the Gulf of Mexico, which left thick oil coating the bottom of the ocean.

What makes dilbit different from many other heavy oils, though, is that it includes diluent. Dilbit is composed of about 70 percent bitumen, consisting of very large, heavy molecules, and 30 percent diluent, consisting of very small, light molecules, which can evaporate much more easily than heavy ones. Other heavy oils typically have almost no light components at all. Therefore, we would expect evaporation to occur differently for dilbit compared to other heavy oils.

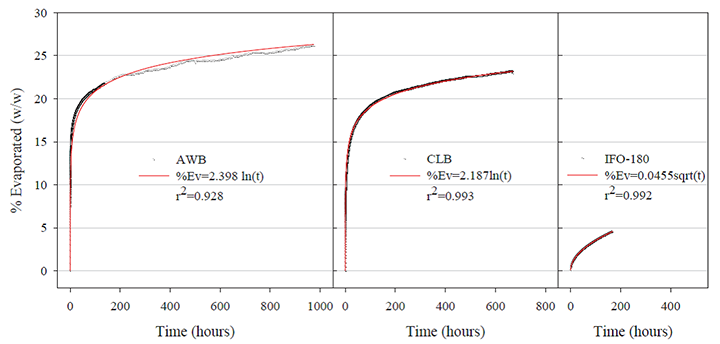

Environment Canada confirmed this to be the case. About four to five times as much of the dilbits evaporated compared to intermediate fuel oil (a heavy oil with no diluent), and the evaporation occurred much faster for dilbit than for intermediate fuel oil in their study. Evaporation transports toxic components of the dilbit into the air, creating a short-term exposure hazard for spill responders and assessment scientists at the site of the spill, which was the case at the 2010 Enbridge spill.

Since the light molecules evaporate after dilbit spills, the leftover residue is even denser than what was spilled initially. Environment Canada, Witt O'Brien's/Polaris/WCMRC, and SL Ross measured the increase in dilbit density over time as it weathered, finding dilbit density increased over time and eventually reached approximately the same density as freshwater.

These studies also found most of the increase in density takes place in the first day or two. What this tells us is that the early hours and days of a dilbit spill are extremely important, and there is only a short window of time before the oil becomes heavier and may become harder to clean up as it sinks below the water surface.

Unfortunately, there can be substantial confusion in the early hours and days of a spill. Was the spilled material dilbit or conventional heavy crude oil? Universal definitions do not exist for these oil product categories. Different entities sometimes categorize the same products differently. Because of these discrepancies, spill responders and scientists evaluating environmental impacts may get conflicting or hard-to-interpret information in the first few days following a spill.

Lessons from the Enbridge Oil Spill

Initially at the Enbridge oil spill, responders used traditional methods to clean up oil floating on the river’s surface, such as booms, skimmers, and vacuum equipment.

After responders discovered the dilbit had sunk to the sediment at the river's bottom, they developed a variety of tactics to collect the oil: spraying the sediments with water, dragging chains through the sediments, agitating sediments by hand with a rake, and driving back and forth with a tracked vehicle to stir up the sediments and release oil trapped in the mud.

These tactics resulted in submerged oil working its way back up to the water surface, where it could then be collected using sorbent materials to mop up the oily sheen.

While these tactics removed some oil from the environment, they might also cause collateral damage, so the Natural Resource Damage Assessment trustees assessed impacts from the cleanup tactics as well as from the oil itself. This case is still ongoing, and trustees' assessment of those impacts will be described in a Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan after the assessment is complete.

For now, we can learn from the Enbridge spill and help predict some potential environmental impacts of future dilbit spills. We can predict that dilbit will weather (undergo physical and chemical changes) rapidly, becoming very dense and possibly sinking in a matter of days. If the dilbit reaches the sediment bed, it can be very difficult to get it out, and bringing in responders and heavy equipment to recover the oil from the sediments can injure the plants and animals living there.

To plan the cleanup and response and predict the impacts of future dilbit spills, we need more information on dilbit toxicity and on how quickly plants and animals can recover from disturbance. Knowing this information will help us balance the potential impacts of cleanup with the short- and long-term effects of leaving the sunken dilbit in place.