Frozen Hands and Muddy Lagoons: Lessons from Summer Sampling in the Arctic

AUGUST 15, 2013 -- From the relative comfort of her cubicle in Anchorage, Alaska, Alaska Regional Coordinator Dr. Sarah Allan has been working on plans for identifying environmental injuries, through a process known as Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA), in the event of an oil spill in the Arctic. These plans include elaborating on a conceptual model for oil spill impacts and developing methods for assessing exposure to oil chemicals and injuries to natural resources in the Arctic. During the last week of July, she had the opportunity to test some of those plans in the decidedly less comfortable but much more spectacular Alaskan Arctic. The Assessment and Restoration Division's ongoing effort to plan for damage assessment in the Arctic is motivated in part by growing industrial activity and vessel traffic in Arctic waters as sea ice decreases. We recognize that the risk of an oil spill in the Arctic is increasing and that conducting spill response and damage assessment in this remote, harsh, and unique region of the world presents a myriad of logistical and scientific challenges—making planning absolutely necessary.

Chasing Snails Under Ice

To test these plans, Allan joined the Arctic Coastal Ecosystem Survey team from NOAA's Alaska Fisheries Science Center for a week on Alaska's North Slope. The goal was to develop and improve techniques for assessing pollutant exposure and resulting injury, which could be used to assess environmental injuries after an oil spill in the Alaskan Arctic. Their team worked in nearshore areas around Barrow, Alaska, which is the northernmost community in the United States. Along much of the arctic coast, the nearshore areas include estuarine lagoons and the shorelines of the barrier islands that define the lagoons. These nearshore areas are important habitat for a diversity of shellfish, migratory birds, and different life stages of fish, which in turn serve as prey for marine mammals and as a subsistence food source for local communities. Though the lagoons and coastline are covered in ice for up to 10 months of the year, they are highly productive habitats for an array of organisms during the brief arctic summer.

Before heading out into the cold, Allan reviewed research on the habitats, organisms, and food webs in the nearshore areas of the Arctic. Though research on these ecosystems is somewhat limited, she looked for information about which species might be present, likely to be exposed to oil chemicals in the event of a spill, and useful for assessing injury to natural resources. She focused on larval fish and adult fish, carnivorous snails, and clams, which are important but vulnerable parts of Alaska's lagoon and nearshore ecosystems. Next, Allan began thinking about how to capture these organisms—how would you sample a snail that is hunting for prey under sea ice that was still present in July?

Even Catching Nothing Reveals Something

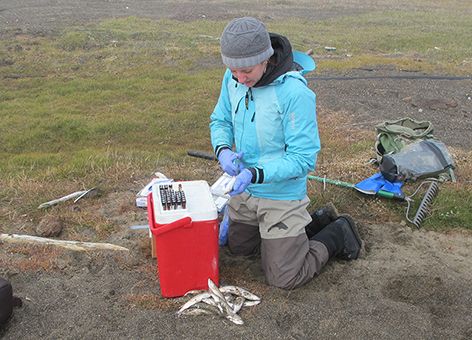

Allan tested a number of techniques for capturing fish and shellfish, including using a rake, a beam trawl that drags along the bottom and collects organisms in an attached net, and a grab sampler that scoops up sediment along with the organisms on and in it. She helped the NOAA Fisheries team sample fish with a beach seine, which is a long net with floats on top and weights on the bottom that they deployed with the help of a small inflatable boat. Seining proved to be effective for capturing large numbers of adult and juvenile fish in the lagoons and nearshore sites, as well as snail larvae at one sampling site.

Capturing snails and clams proved much harder for a number of reasons. The bottoms of the lagoons were muddy, with patches of tundra that foiled the sampling tools she tried. Though the equipment worked better on the ocean, rather than the lagoon, side, she did not capture any of the snails or clams she was targeting. Past research indicates that clams and snails in the Arctic have a patchy distribution, which could explain why her efforts didn't turn up many samples. Though she only worked in a small area of the Arctic, this information about species distribution, capture methods, and level of effort adds to our planning efforts. It helps assure that, in the event of a spill, we appropriately focus our initial efforts and study plans and make realistic decisions about how much we can sample and with what priority.

Capturing What's Ephemeral

Another element of Allan's field work on Alaska’s North Slope was to test high-priority ephemeral data collection protocols that her team has been developing for Natural Resource Damage Assessment in the Arctic. Ephemeral data are information that changes quickly over time, such as the concentration of oil chemicals in the water after a spill or the presence of certain species and life stages in an impacted area. Because these data are ephemeral, it is important to collect them as quickly as possible in the first few days and weeks after an oil spill so that we can accurately assess the resulting exposure and injury. Having tried-and-true protocols for collecting this information helps prepare us to do this quickly after a spill and at the high standard needed for the damage assessment process.

Allan tested the draft protocols for sampling water, sediment, shellfish, fish, and fish bile. This testing brought to light a number of Arctic-specific modifications that need to be made to the protocols, as well as the need to develop additional protocols for unique arctic habitats.

Weather Days

Though Allan was prepared to deal with Alaska's notoriously horrific swarms of mosquitoes, it was actually the cold temperatures, snow, sea ice, and high winds that proved to be more of a challenge on this trip. These "mild" summer conditions made even simple tasks, like writing on a sample label, difficult and time consuming with numb hands, a frozen pen, a wet label, and wind trying to blow away the clipboard. She took advantage of the "weather days," when wind and fog made working on the water too dangerous, to meet with local scientists and borough authorities to discuss Arctic oil spill response and Natural Resource Damage Assessment. Unlike most other villages in the Alaskan Arctic, Barrow has some private, university, borough, state, and federal research facilities. This trip was a valuable chance to connect with local experts and learn about research facilities and their capacity for supporting or participating in our work. This field work was an opportunity to put plans for conducting Natural Resource Damage Assessment in the Arctic to the test. Sharing the lessons learned and integrating them into our planning improves our preparedness to do timely and appropriate injury assessments in the event of a spill in the Arctic.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.