How to Restore a Damaged Coral Reef: Undersea Vacuums, Power Washers, and Winter Storms

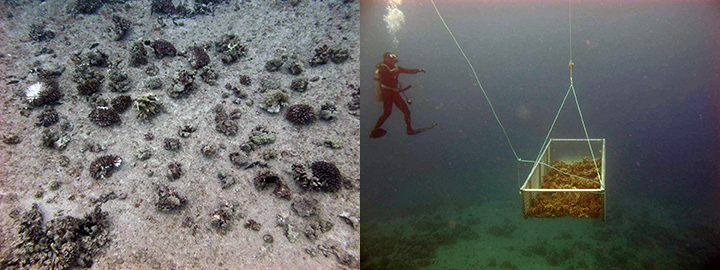

JUNE 3, 2014 -- After a ship runs aground on a coral reef, the ocean bottom becomes a messy place: thickly carpeted with a layer of pulverized coral several feet deep. This was the scene underwater off the Hawaiian island of Oahu in February of 2010. On February 5, the cargo ship M/V Vogetrader ran aground and was later removed from a coral reef in the brilliant blue waters of Kalaeloa/Barber's Point Harbor. NOAA and our partners suited up in dive gear and got to work restoring this damaged reef, beginning work in October 2013 and wrapping up in April 2014. While a few young corals have begun to repopulate this area in the time since the grounding, even fast-growing corals grow less than half an inch per year. The ones there now are mostly smaller than a golf ball and the seafloor was still covered in crushed and dislodged corals. These broken corals could be swept up and knocked around by strong currents or waves, potentially causing further injury to the recovering reef. This risk was why we pursued emergency restoration activities for the reef. What we didn't expect was how a strong winter storm would actually help our restoration work in a way that perhaps has never before been done.

How Do You Start Fixing a Damaged Reef?

First, we had to get the lay of the (underwater) land, using acoustic technology to map exactly where the coral rubble was located and determine the size of the affected area. Next, our team of trained scuba divers gathered any live corals and coral fragments and transported them a short distance away from where they would be removing the rubble. Then, we were ready to clean up the mess from the grounding and response activity and create a place on the seafloor where corals could thrive. Divers set up an undersea vacuum on the bottom of the ocean, which looks like a giant hose reaching 35 feet down from a boat to the seafloor. It gently lifted rubble up through the hose—gently, because we wanted to avoid ripping everything off of the seafloor. Eventually, our team would remove nearly 800 tons (more than 700 metric tons) of debris from the area hit by the ship.

Unexpected Gifts from a Powerful Storm

In the middle of this work, the area experienced a powerful winter storm, yielding 10-year high winter swells that reduced visibility underwater and temporarily halted the restoration work. When the divers returned after the storm subsided, they were greeted by a disappointing discovery: the cache of small coral remnants they had stockpiled to reattach to the sea bottom was gone. The swells had scoured the seafloor and scattered what they had gathered.

But looking around, the divers realized that the energetic storm had broken off and dislodged a number of large corals nearby. Corals that were bigger than those they lost and which otherwise would have died as a result of the storm. With permission from the State of Hawaii, they picked up some of these large, naturally detached corals, which were in good condition, and used them as donor corals to finish the restoration project. Finding suitable donor corals is one of the most difficult aspects of coral restoration. This may have been the first time people have been able to take advantage of a naturally destructive event to restore corals damaged by a ship grounding.

A Reef Restored

Once our team transported the donor corals to the restoration site a few hundred yards away, they scraped the seafloor, at first by hand and then with a power washer, to prepare it for reattaching the corals. Using a cement mixer on a 70-foot-long boat, they mixed enough cement to secure 643 corals to the seafloor.

While originally planning to reattach 1,200 coral colonies, the storm-blown corals were so large (and therefore so much more valuable to the recovering habitat) that the divers ran out of space to reattach the corals. In the end, they didn't replace these colonies in the exact same area that they removed the coral rubble. When the ship hit the reef, it displaced about three feet of reef, exposing a fragmented, crumbly surface below. They left this area open for young corals to repopulate but traveled a little higher up on the reef shelf to reattach the larger corals on a more secure surface, one only lightly scraped by the ship. The results so far are encouraging. Very few corals were lost during the moving and cementing process, and the diversity of coral species in the reattachment area closely reflects what is seen in unaffected reefs nearby. These include the common coral species of the genus Montipora (rice coral), Porites lobata (lobe coral), and Pocillopora meandrina (cauliflower coral). As soon as the divers finished cleaning and cementing the corals to the ocean floor, reef fish started moving in, apparently pleased with the state of their new home. But our work isn't done yet. We'll be keeping an eye on these corals as they recover, with plans to return for monitoring dives in six months and one year. In addition, we'll be working with our partners to develop even more projects to help restore these beautiful and important parts of Hawaii's undersea environment. UPDATE: See this restoration work come to life in a video documenting the process and find out how transplanted corals have been recovering. NOAA Fisheries Biologist Matt Parry contributed to this story and this restoration work.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.