Latest Research Finds Serious Heart Troubles When Oil and Young Tuna Mix

PUBLISHED MARCH 26, 2014 | UPDATED APRIL 9, 2015 -- In May of 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon rig was drilling for oil in the open waters of the Gulf of Mexico, schools of tuna and other large fish would have been moving into the northern Gulf. This is where, each spring and summer, they lay delicate, transparent eggs that float and hatch near the ocean surface. After the oil well suffered a catastrophic blowout and released 3.19 million barrels of oil into the Gulf, these fish eggs may have been exposed to the huge slicks of oil floating up through the same warm waters. An international team of researchers from NOAA, Stanford University, the University of Miami, and Australia recently published a study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences exploring what happens when tuna mix with oil early in life. "What we're interested in is how the Deepwater Horizon accident in the Gulf of Mexico would have impacted open-ocean fishes that spawn in this region, such as tunas, marlins, and swordfishes," said Stanford University scientist Barbara Block. This study is part of ongoing research to determine how the waters, lands, and life of the Gulf of Mexico were harmed by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and response. It also builds on decades of research examining the impacts of crude oil on fish, which began after the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska. Based on those studies, NOAA and the rest of the research team knew that crude oil—including oil from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (Incardona et al. 2013)—was toxic to young fish and it would be important to look carefully at their developing hearts. "One of the most important findings was the discovery that the developing fish heart is very sensitive to certain chemicals derived from crude oil," said Nat Scholz of NOAA's Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

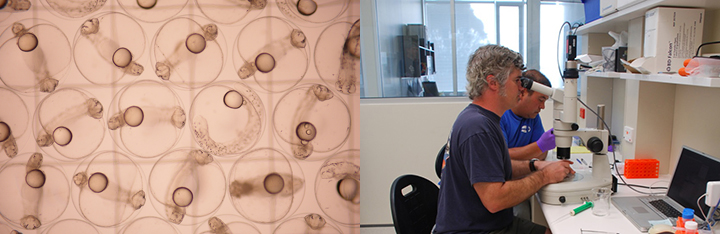

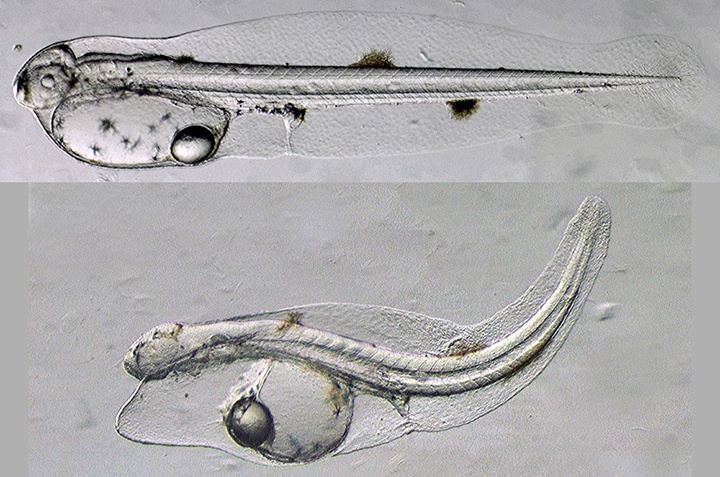

This is why in this latest study they examined oil's impacts on young bluefin tuna, yellowfin tuna, and amberjack, all large fish that hunt at the top of the food chain and reproduce in the warm waters of the open ocean. The researchers exposed fertilized fish eggs to small droplets of crude oil collected from the surface and the wellhead from the Deepwater Horizon spill, using concentrations comparable to those during the spill. Next, they put the transparent eggs and young fish under the microscope to observe the oil's impacts at different stages of development. Using a technology similar to doing ultrasounds on humans, the researchers were able create a digital record of the fishes' beating hearts. All three species of fish showed dramatic effects from the oil, regardless of how weathered (broken down) it was. Severely malformed and malfunctioning hearts was the most severe impact. Depending on the oil concentration, the developing fish had slow and irregular heartbeats and excess fluid around the heart. Other serious effects, including spine, eye, and jaw deformities, were a result of this heart failure. (Incardona et al. 2014 [PDF])

"Crude oil shuts down key cellular processes in fish heart cells that regulate beat-to-beat function," noted Block, referencing another study by this team (Brette et al. 2014). As the oil concentration, particularly the levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), went up, so did the severity of the effects on the fish. Severely affected fish with heart defects are unlikely to survive. Others looked normal on the outside but had underlying issues like irregular heartbeats. This could mean that while some fish survived directly swimming through oil, heart conditions could follow them through life, impairing their (very important) swimming ability and perhaps leading to an earlier-than-natural death. "The heart is one of the first organs to appear, and it starts beating before it's completely built," said NOAA Fisheries biologist John Incardona. "Anything that alters heart rhythm during embryonic development will likely impact the final shape of the heart and the ability of the adult fish to survive in the wild." Even at low levels, oil can have severe effects on young fish, not only in the short-term but throughout the course of their lives. This is why the research team, composed of scientists from NOAA, Stanford University, and the University of Miami, is studying fish exposed to low levels of crude oil as embryos that subsequently grow into juveniles and adults in clean water. Initial research has shown that subtle disruptions of the embryonic heartbeat can produce permanent changes in heart shape that negatively affect swimming performance and other behaviors critical for fish survival. The team has shown similar underlying effects on juvenile mahi mahi (Mager et al. 2014), and studies are ongoing using zebrafish. These subtle but serious impacts are a lesson still obvious in the recovery of marine animals and habitats still happening 25 years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Find the most up-to-date summary of NOAA-funded research on crude oil's potential effects on fish in the Gulf Mexico. By Ashley Braun, NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration Web Editor.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.