Little 'Bugs' Can Spread Big Pollution Through Contaminated Rivers

This post was originally published April 10, 2014.

When we think of natural resources harmed by pesticides, toxic chemicals, and oil spills, most of us probably envision soaring birds or adorable river otters. Some of us may consider creatures below the water's surface, like the salmon and other fish that the more charismatic animals eat, and that we like to eat ourselves. But it's rare that we spend much time imagining what contamination means for the smaller organisms that we don't see, or can't see without a microscope.

The tiny creatures that live in the "benthos"—the mud, sand, and stones at the bottoms of rivers—are called benthic macroinvertebrates. Sometimes mistakenly called "bugs," the benthic macroinvertebrate community actually includes a variety of animals like snails, clams, and worms, in addition to insects like mayflies, caddisflies, and midges. They play several important roles in an ecosystem. They help cycle and filter nutrients and they are a major food source for fish and other animals. Though we don't see them often, benthic macroinvertebrates play an extremely important role in river ecosystems.

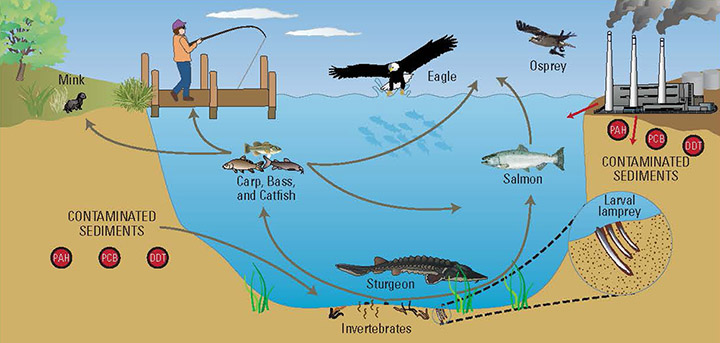

In polluted rivers, such as the lower Willamette River in Portland, Oregon, these creatures serve as food web pathways for legacy contaminants like PCBs and DDT. Because benthic macroinvertebrates live and feed in close contact with contaminated muck, they are prone to accumulation of contaminants in their bodies. They are, in turn, eaten by predators and it is in this way that contaminants move "up" through the food web to larger, more easily recognizable animals such as sturgeon, mink, and bald eagles.

The image above depicts some of the pathways that contaminants follow as they move up through the food web in Oregon’s Portland Harbor. Benthic macroinvertebrates are at the bottom of the food web. They are eaten by larger animals, like salmon, sturgeon, and bass. Those fish are then eaten by birds (like osprey and eagle), mammals (like mink), and people.

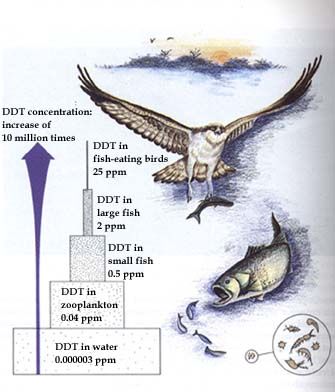

As PCB and DDT contamination makes its way up the food chain through these organisms, it is stored in their fat and biomagnified, meaning that the level of contamination you find in a large organism like an osprey is many times more than what you would find in a single water-dwelling insect. This is because an osprey eats many fish in its lifetime, and each of those fish eats many benthic macroinvertebrates. Therefore, a relatively small amount of contamination in a single insect accumulates to a large amount of contamination in a bird or mammal that may have never eaten an insect directly.

According to a graphic developed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, DDT concentrations biomagnify 10 million times as they move up the food chain. Benthic macroinvertebrates can be used by people to assess water quality. Certain types of benthic macroinvertebrates cannot tolerate pollution, whereas others are extremely tolerant of it. For example, if you were to turn over a few stones in a Northwest streambed and find caddisfly nymphs (pictured below encased in tiny pebbles), you would have an indication of good water quality. Caddisflies are very sensitive to poor water quality conditions.

Surveys in Portland Harbor have shown that we have a pretty simple and uniform benthic macroinvertebrate population in the area. As you might expect, it is mostly made up of pollution-tolerant species. NOAA Restoration Center staff are leading restoration planning efforts at Portland Harbor and it is our hope that once cleanup and restoration projects are completed, we will see a more diverse assemblage of benthic macroinvertebrates in the Lower Willamette River.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.