Oil Seeps, Shipwrecks, and Surfers Ride the Waves in California

APRIL 1, 2014 -- What do natural oil seeps, shipwrecks, and surfers have in common? The quick answer: tarballs and oceanography. The long answer: It's a longer story ...

A rash of tarballs, which are thick, sticky, and small pieces of partially broken-down oil, washed ashore at Half Moon Bay, Calif., south of San Francisco back in mid-February.

This isn't an unusual occurrence this time of year, but several of those involved in spill response, including NOAA Scientific Support Coordinator Jordan Stout, still received phone calls about them and decided to check things out.

Winds and ocean currents are the primary movers of floating oil. A quick look at conditions around that time indicated that floating stuff (like oil) would have generally been moving northwards up the coast.

Off of Monterey Bay, there had been prolonged winds out of the south several times since December, including just prior to the tarballs' arrival. Coastal currents at the time also showed the ocean's surface waters moving generally up the coast. Then, just hours before their arrival, winds switched direction and started coming out of the west-northwest, pushing the tarballs ashore.

Seeps and Shipwrecks

It's common winter conditions like that, combined with the many natural oil seeps of southern California, that often result in tarballs naturally coming ashore in central and northern California. Wintertime tarballs are not unheard of in this area and people weren't terribly concerned. Even so, some of the tarballs were relatively "fresh" and heavy weather and seas had rolled through during a storm the previous weekend. This got some people thinking about the shipwreck S/S Jacob Luckenbach, a freighter which sank near San Francisco in 1953 and began leaking oil since at least 1992.

When salvage divers were removing oil from the Luckenbach back in 2002, they reported feeling surges along the bottom under some wave conditions. The wreck is 468 feet long, lying in about 175 feet of water and is roughly 20 miles northwest of Half Moon Bay. Could this or another nearby wreck have been jostled by the previous weekend’s storm and produced some of the tarballs now coming ashore?

Making Waves

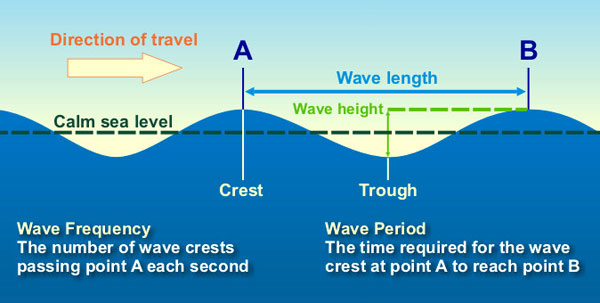

Discussions with the oceanographers in NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration provided Jordan Stout with some key kernels of wisdom about what might have happened. First, the height of a wave influences the degree of effects beneath the ocean surface, but the wave length determines how deep those effects go. So, big waves with long wavelengths have greater influence at greater depths than smaller waves with shorter wavelengths.

Second, waves in deep water cause effects at depths half their length. This means that a wave with a length of 100 meters can be felt to a depth of 50 meters. That was great stuff, thought Stout. But the data buoys off of California, if they collect any wave data at all, only collect wave height and period (the time it takes a wave to move from one high or low point to the next) but not wave length. So, now what?

As it turns out, this office's excellent oceanographers also have a rule of thumb for calculating wave length from this information: a wave with a 10-second period has a wave length of about 100 meters in deep water. So, that same 10-second wave would be felt at 50 meters, which is similar to the depth of the shipwreck Jacob Luckenbach (54 meters or 175 feet).

Looking at nearby data buoys, significant wave heights during the previous weekend’s storm topped out at 2.8 meters (about 9 feet) with a 9-second period. So, the sunken Luckenbach may have actually "felt" the storm a little bit, but probably not enough to cause a spill of any oil remaining on board it.

Riding Waves

Even so, just two weeks before the tarballs came ashore, waves in the area were much, much bigger. The biggest waves the area had seen so far in 2014, in fact: more than 4 meters (13 feet) high, with a 24-second period. If the Luckenbach had been jostled by any waves at all in 2014, it likely would have been from those waves in late January, and yet there were no reports of tarballs (fresh or otherwise) even though winds were blowing towards shore for about a week afterwards. This led Stout to conclude that the recent increase in tarballs came from somewhere other than a nearby shipwreck.

Where do surfers fit in all this? That day in late January when the shipwreck S/S Jacob Luckenbach was being knocked around by the biggest waves of 2014 was the day of the Mavericks Invitational surf contest in Half Moon Bay. People came from all over to ride those big waves—and according to Stout, it was amazing!

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.