Using Big Data to Restore the Gulf of Mexico

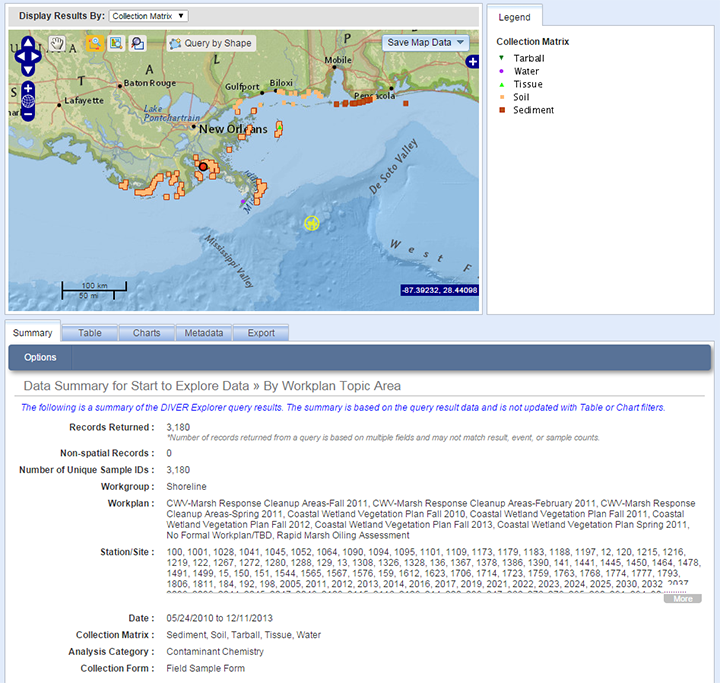

This is a post by Ocean Conservancy's Elizabeth Fetherston. JUNE 15, 2015 -- If I ask you to close your eyes and picture "protection for marine species," you might immediately think of brave rescuers disentangling whales from fishing gear. Or maybe you would imagine the army of volunteers who seek out and protect sea turtle nests. Both are noble and worthwhile endeavors. But 10 years of ocean conservation in the southeast United States has taught me that protecting marine species doesn't just look like the heroic rescue of adorable species in need. I've learned that it also looks like the screen of 1s and 0s from the movie The Matrix. Let me explain. Much of what goes on with marine life in the Gulf of Mexico—and much of the rest of the ocean—is too dark and distant to see and measure easily or directly. Whales and fish and turtles move around a lot. This makes it difficult to collect information on how many there are in the Gulf and how well those populations are doing. In order to assess their health, you need to know where these marine species go, what they eat, why they spend time in certain areas (for food, shelter, or breeding?), and more. This information may come from a number of places—state agencies, universities, volunteer programs, you name it—and be stored in a number of different file formats. Until recently, there was no real way to combine all of these disparate pixels of information into a coherent picture of, for instance, a day in the life of a sea turtle. DIVER, NOAA's new website for Deepwater Horizon assessment data, gives us the tools to do just that. Data information and integration systems like DIVER put all of that information in one place at one time, allowing you to look for causes and effects that you might not have ever known were there and then use that information to better manage species recovery. These data give us a new kind of power for protecting marine species. Of course, this idea is far from new. For years, NOAA and ocean advocates have both been talking about a concept known as "ecosystem-based management" for marine species. Put simply, ecosystem-based management is a way to find out what happens to the larger tapestry if you pull on one of the threads woven into it. For example, if you remove too many baitfish from the ecosystem, will the predatory fish and wildlife have enough to eat? If you have too little freshwater coming through the estuary into the Gulf, will nearby oyster and seagrass habitats survive? In order to make effective and efficient management decisions in the face of these kinds of complex questions, it helps to have all of the relevant information working together in a single place, in a common language, and in a central format.

So is data management the key to achieving species conservation in the Gulf of Mexico? It just might be. Systems like DIVER are set up to take advantage of quantum leaps in computing power that were not available to the field of environmental conservation 10 years ago. These advances give DIVER the ability to accept reams of diverse and seemingly unrelated pieces of information and, over time, turn them into insight about the nature and location of the greatest threats to marine wildlife. The rising tide of restoration work and research in the Gulf of Mexico will bring unprecedented volumes of data that should—and now can—be used to design and execute conservation strategies with the most impact for ocean life in our region. Ocean Conservancy is excited about the opportunity for systems like DIVER to kick off a new era in how we examine information and solve problems. Elizabeth Fetherston is a Marine Restoration Strategist with Ocean Conservancy. She is based in St. Petersburg, Florida and works to ensure restoration from the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster is science-based, integrated across political boundaries, fully funded, and inclusive of offshore Gulf waters where the spill originated. The views expressed here reflect those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) or the federal government.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.