In Wake of Japan's 2011 Tsunami, Citizen Scientists Comb California Beaches Counting Debris

SEPTEMBER 11, 2015 -- It all started nearly five years ago on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. A devastating earthquake and tsunami rocked Japan in 2011, ultimately sweeping millions of tons of debris from the coastline into the ocean. But it wasn't until June the following year, in 2012, that a 66-foot-long Japanese dock settled on the Oregon coast and reminded the world how the ocean connects us. NOAA's Kate Bimrose explained how this event and the resulting concern over other large or hazardous items of Japanese debris spurred the start of NOAA monitoring programs on beaches up and down the West Coast and Pacific islands. She coordinates the program that monitors marine debris in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary off the north-central California coast. Thanks to funding from NOAA's Marine Debris Program, the first surveys in this sanctuary near San Francisco took place in July 2012, a month after the Oregon dock made an appearance. No previous baseline data on debris existed for the shores along this California sanctuary. The only way anyone would know if Japan tsunami marine debris started arriving is by counting how much marine debris was already showing up there on a regular basis.

Training a Wave of Citizen Scientists

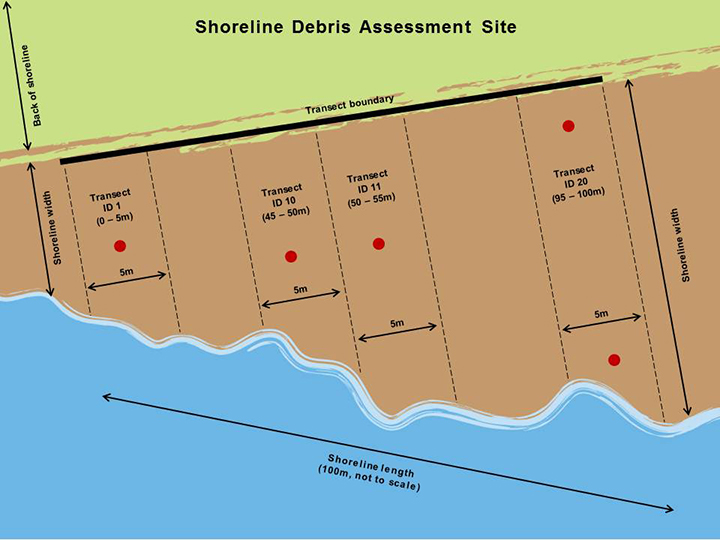

To find out how much trash and other manmade debris was washing up, Bimrose trained a small group of dedicated, volunteer "citizen scientists" to perform monthly surveys at four regular California beach sites. Three are located in Point Reyes National Seashore and one is in Año Nuevo State Park, but all are fed by the waters of the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. Following NOAA Marine Debris Program monitoring protocols, once a month two volunteers head to the same 100 meter (328 foot) stretch of beach, using GPS coordinates to locate it. Next, they randomly pick four sections, each five meters (nearly 16.5 feet) long, to survey that day. This ensures they cover 20 percent of the area each time. For those areas, the volunteers record every piece of trash they find that is at least the size of a bottle cap, or roughly an inch long. Having this size standard increases the reliability of the data being collected, providing a more accurate picture of what the ocean is bringing to each beach. NOAA is confident that volunteers are able to scan the sand and find the majority of items larger than an inch sitting on the surface of the beach.

Taking Things to the Next Level

All of the data volunteers gather—from number of items to types of material found—gets entered into a national online database, which will allow NOAA to determine trends in where, what, and how much marine debris is showing up. Leaving the items behind reveals how debris concentrates and persists on shorelines, information which is lost when debris is hauled off the beach. While gathering this information is useful, Bimrose admitted to one sticking point for her: none of the debris is cleaned up from these four beach locations. "We want to be able to remove the debris," she said. "It's painful for all my volunteers to be out there and record it and not remove it." However, the good news is that a June 2015 expansion to this monitoring program has added two new beach locations to the rotation, and after volunteers record the debris there, they pack it out. In addition, Bimrose takes out larger groups of one-time volunteers to those locations and trains them on site, creating a broader educational reach for the program. Bimrose hopes to recruit local school groups as well as businesses to volunteer. Before each survey at the new locations, she introduces the sanctuary and the monitoring program, while passing around mason jars filled with the trash collected at past surveys to give volunteers an idea of what to expect. These new monitoring sites receive more recreational use than the previous ones, and at least for the one at Ocean Beach, a heavily used shoreline in the heart of San Francisco, that means finding a lot more consumer trash left on the beach. From clothes and cigarette butts to food wrappers and even toilet paper, the surveys at Ocean Beach are markedly different from those surveys further north at Drakes Beach, the other new site. There, volunteers count and remove mostly small, hard fragments of plastic that appear worn down by sun and sea, indicating the majority of the debris there is brought to shore by the waves, not beachgoers.

Survey Says

After four years of monitoring and roughly 150 surveys, what have they found so far on the north-central California coast? More than 5,000 debris items recorded in all, which, as Bimrose said, is "a good amount but not too crazy." Expanding to six survey sites from four only increases what they can learn about debris patterns in this area. As more data roll in, NOAA will able to outline the regional scope of the problem and see patterns between seasons, years, categories, and locations of debris accumulation. One thing that is likely not to change, however, is that plastic debris dominates. It constitutes about 80 percent of the trash found at all sites. While volunteers occasionally turn up debris bearing Asian characters, no items reported from this program have been confirmed from the 2011 Japan tsunami. Through other partners associated with beach cleanups however, three pieces of Japan tsunami debris have been confirmed in California. The most recent was a large green pallet with Kanji lettering that landed on Mussel Beach just south of San Francisco. The discovery reinforces the importance of continuing to monitor debris along sanctuary beaches and shows us how items can persist in the ocean for years before sinking, breaking up, or landing on shore. Another unusual example linking a piece of debris to the exact event that released it occurred in 2012. During a training run for the America’ Cup sailing race, an $8 million boat capsized and broke apart in San Francisco Bay on October 16, 2012. Two months later, one of Bimrose's volunteers discovered a piece of insulation from that boat on a beach about 60 miles north. Every month, Bimrose tags along with at least one pair of volunteers for their survey of one of the four "survey-only" beach sites. On one such occasion, one volunteer, an older gentleman, brought along his wife, who was puzzled by her husband’s constant chatter about "his" beach. According to Bimrose, a lot of the surveys could be considered rather clean or even monotonous. But even so, after a day walking and counting with him, the volunteer's wife told her, "I totally get it, why he comes out here and rearranges his schedule to do this."