When Ships Threaten Corals in the Caribbean, NOAA Dives to Their Rescue

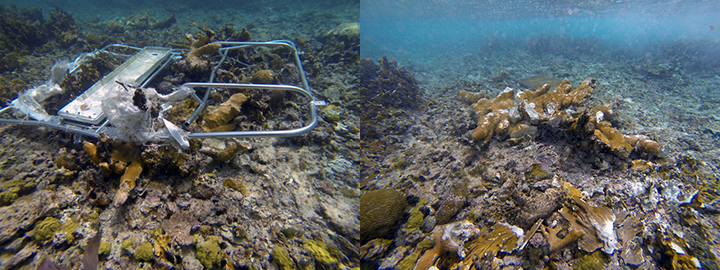

DECEMBER 2, 2014 -- Growing less than a quarter inch per year, the elaborate coral reefs off the south coast of Puerto Rico originally took thousands of years to form. And over the course of two days in late April 2006, portions of them were ground into dust. The tanker Margara ran aground on these reefs near the entrance to Guayanilla Bay. Then, in the attempt to remove and refloat the ship, it made contact with the bottom several times and became grounded again. By the end, roughly two acres of coral were lost or injured. The seafloor was flattened and delicate corals crushed. Even today, a carpet of broken coral and rock remains in part of the area. This loose rubble becomes stirred up during storms, smothering young coral and preventing the reef's full recovery. NOAA and the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources have been working on a restoration plan for this area, a draft of which they released for public comment in September 2014 [PDF]. In order to stabilize these rubble fields and return topographic complexity to the flattened seafloor, they propose placing limestone and large boulders over the rubble. Next, they plan to transplant corals to the area to speed up recovery. This is in addition to two years of emergency restoration actions, which included stabilizing some of the large rubble, reattaching around 10,500 corals, and monitoring the slow comeback and survival of young coral. In the future, even more restoration will be in the works to make up for the full suite of environmental impacts from this incident.

Caribbean Cruising for a Bruising

Unfortunately, the story of the Margara is not an unusual one. In 2014 alone, NOAA received reports of 37 vessel groundings in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. About half of these cases threatened corals, prompting NOAA's Restoration Center to send divers to investigate. After a ship gets stuck on a coral reef, the first step for NOAA is assessing the situation underwater. If the vessel hasn't been removed yet, NOAA often provides the salvage company with information such as known coral locations and water depths, which helps them determine how to remove the ship with minimal further damage to corals. Sometimes that means temporarily removing corals to protect them during salvage or figuring out areas to avoid hitting as the ship is extracted. Once the ship is gone, NOAA divers estimate how many corals and which species were affected, as well as how deep the damage was to the structure of the reef itself. This gives them an idea of the scale of restoration needed. For example, if less than 100 corals were injured, restoration likely will take a few days. On the other hand, dealing with thousands of corals may take months.

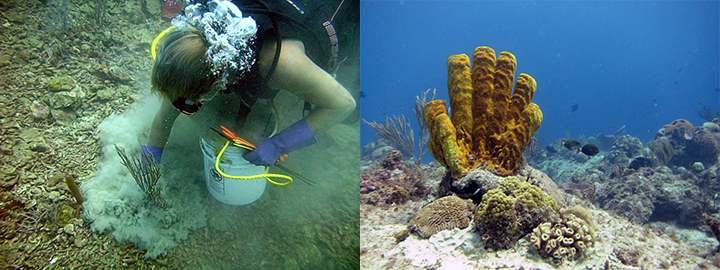

NOAA already has done some form of restoration at two-thirds of the 18 vessel groundings with coral damage in the region this year. They have reattached 2,132 corals to date. What does this look like? At first, it's a lot of preparation. Divers collect the corals and fragments knocked loose by the ship; transport them to a safe, stable underwater location where they won't be moved around; and dig out any corals buried in debris. When NOAA is ready to reattach corals, divers clear the transplant area (sometimes that means using a special undersea vacuum). On the ocean surface, people in a boat mix cement and send it down in five-gallon buckets to the divers below. Working with nails, rebar, and cement, the divers carefully reattach the corals to the seafloor, with the cement solidifying in a couple hours.

Protecting Coral, From the Law to the High Seas

Nearly a third of the total reported groundings in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands this year have involved corals listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. In previous years, only 10 percent of the groundings involved threatened corals. What changed this year was the Endangered Species Act listing of five additional coral species in the Caribbean. Another form of protection for corals is installing buoys to mark the location of reefs in areas where ships keep grounding on them. Since these navigational aids were put in place at one vulnerable site in Culebra, Puerto Rico, this summer, NOAA hasn't been called in to an incident there yet.

But restoring coral reefs after a ship grounding almost wouldn't be possible without coral nurseries. Here, NOAA is able to regrow and rehabilitate coral, a technique being used at the site of the T/V Margara grounding. Stay tuned because we'll be going more in depth on coral nurseries, what they look like, and how they help us restore these amazingly diverse ocean habitats.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.