Where Are the Pacific Garbage Patches?

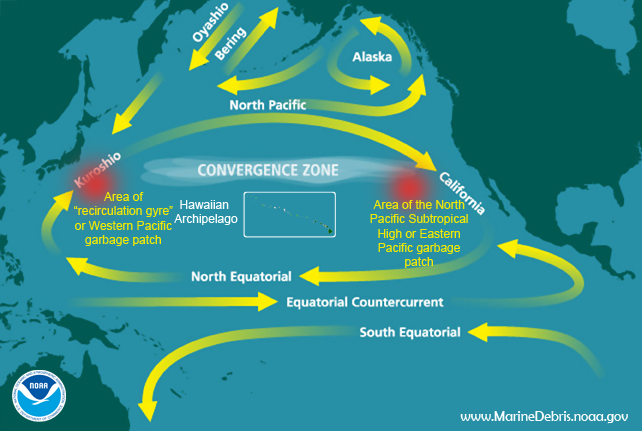

FEB. 7, 2013 — The Pacific Ocean is massive. It's the world's largest and deepest ocean, and if you gathered up all of the Earth's continents, these land masses would fit into the Pacific basin with a space the size of Africa to spare. While the Pacific Ocean holds more than half of the planet's free water, it also unfortunately holds a lot of the planet's garbage (much of it plastic). But that trash isn't spread evenly across the Pacific Ocean; a great deal of it ends up suspended in what are commonly referred to as "garbage patches." A combination of oceanic and atmospheric forces causes trash, free-floating sea life (for example, algae, plankton, and seaweed), and a variety of other things to collect in concentrations in certain parts of the ocean. In the Pacific Ocean, there are actually a few "Pacific garbage patches" of varying sizes as well as other locations where marine debris is known to accumulate.

The Eastern Pacific Garbage Patch (aka "Great Pacific Garbage Patch")

In most cases when people talk about the "Great Pacific Garbage Patch," they are referring to the Eastern Pacific garbage patch. This is located in a constantly moving and changing swirl of water roughly midway between Hawaii and California, in an atmospheric area known as the North Pacific Subtropical High. NOAA National Weather Service meteorologist Ted Buehner describes the North Pacific High as involving "a broad area of sinking air resulting in higher atmospheric pressure, drier warmer temperatures and generally fair weather (as a result of the sinking air)." This high pressure area remains in a semi-permanent state, affecting the movement of the ocean below. "Winds with high pressure tend to be light(er) and blow clockwise in the northern hemisphere out over the open ocean," according to Buehner. As a result, plastic and other debris floating at sea tend to get swept into the calm inner area of the North Pacific High, where the debris becomes trapped by oceanic and atmospheric forces and builds up at higher concentrations than surrounding waters. Over time, this has earned the area the nickname "garbage patch"—although the exact content, size, and location of the associated marine debris accumulations are still difficult to pin down.

The Western Pacific Garbage Patch

On the opposite side of the Pacific Ocean, there is another so-called "garbage patch," or area of marine debris buildup, off the southeast coast of Japan. This is the lesser known and studied, Western Pacific garbage patch. Southeast of the Kuroshio Extension (ocean current), researchers believe that this garbage patch is a small "recirculation gyre," an area of clockwise-rotating water, much like an ocean eddy (Howell et al., 2012).

North Pacific Subtropical Convergence Zone

While not called a "garbage patch," the North Pacific Subtropical Convergence Zone is another place in the Pacific Ocean where researchers have documented concentrations of marine debris. A combination of oceanic and atmospheric forces create this convergence zone, which is positioned north of the Hawaiian Islands but moves seasonally and dips even farther south toward Hawaii during El Niño years (Morishige et al., 2007, Pichel et al., 2007). The North Pacific Convergence Zone is an area where many open-water marine species live, feed, or migrate and where debris has been known to accumulate (Young et al. 2009). Hawaii's islands and atolls end up catching a notable amount of marine debris as a result of this zone dipping southward closer to the archipelago (Donohue et al. 2001, Pichel et al., 2007). But the Pacific Ocean isn't the only ocean with marine debris troubles. Trash from humans is found in every ocean, from the Arctic (Bergmann and Klages, 2012) to the Antarctic (Eriksson et al., 2013), and similar oceanic processes form high-concentration areas where debris gathers in the Atlantic Ocean and elsewhere.

You can help keep trash from becoming marine debris by (of course) reducing, reusing, and recycling; by downloading the NOAA Marine Debris Tracker app for your smartphone; and by learning more at the NOAA Marine Debris Program's website.

Literature Cited

Bergmann, M. and M. Klages. 2012. Increase of litter at the Arctic deep-sea observatory HAUSGARTEN. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 64: 2734-2741.

Donohue, M.J., R.C. Boland, C.M. Sramek, and G.A Antonelis. 2001. Derelict fishing gear in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands: diving surveys and debris removal in 1999 confirm threat to coral reef ecosystems. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 42 (12): 1301-1312.

Eriksson, C., H. Burton, S. Fitch, M. Schulz, and J. van den Hoff. 2013. Daily accumulation rates of marine debris on sub-Antarctic island beaches. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 66: 199-208.

Howell, E., S. Bograd, C. Morishige, M. Seki, and J. Polovina. 2012. On North Pacific circulation and associated marine debris concentration. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 65: 16-22.

Morishige, C., M. Donohue, E. Flint, C. Swenson, and C. Woolaway. 2007. Factors affecting marine debris deposition at French Frigate Shoals, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument, 1990-2002. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 54: 1162-1169.

Pichel, W.G., J.H. Churnside, T.S. Veenstra, D.G. Foley, K.S. Friedman, R.E. Brainard, J.B. Nicoll, Q. Zheng and P. Clement-Colon. 2007. Marine debris collects within the North Pacific Subtropical Convergence Zone [PDF]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 54: 1207-1211.

Young L. C., C. Vanderlip, D. C. Duffy, V. Afanasyev, and S. A. Shaffer. 2009. Bringing home the trash: do colony-based differences in foraging distribution lead to increased plastic ingestion in Laysan albatrosses? PLoS ONE 4 (10).

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.