How Do You Keep Invasive Species out of America's Largest Marine Reserve?

FEBRUARY 26, 2015 -- From Honolulu, it takes a day and a half to get there by boat.

But Scott Godwin, an expert in the ways "alien" marine life can travel and take hold in new places, knows what is at risk.

He understands perfectly well what might happen if a new species manages to make that journey to the remote and incredible area under his watch.

Godwin works for the Resource Protection Program in NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

Along with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and State of Hawaii, he is charged with protecting Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, a tall order considering that it is one of the largest marine conservation areas in the world.

This monument includes an isolated chain of tropical islands, atolls, and reefs hundreds of miles northwest of the main Hawaiian Islands—appropriately known as the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands—as well as nearly 140,000 square miles of surrounding waters.

The monument is home to a host of rare and unique species, some found exclusively within its borders, as well as some of the healthiest and least disturbed coral reefs on Earth.

And it is Godwin's job to keep it that way. Along with climate change and marine debris, invasive species have been identified as one of the top three threats to this very special place, which, in addition to being a national monument, is also a U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Wildlife Refuge and United Nations World Heritage Site. Fortunately, invasive species also happen to be Godwin's area of expertise.

If new species were to break into the monument's borders—and in some cases, they already have—the risk is of them exhibiting "invasive" behavior. In other words, out-competing the native marine life among the coral reefs and taking the lion’s share of the most valuable resources: food and space.

But considering how remote and expansive the area is—the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands stretch across 1,200 nautical miles and are closed to the general public—how would anything find its way there in the first place?

Yet help from humans is how many species arrive in new environments, including the main Hawaiian Islands, where more than 400 non-native marine species are established. That means ships and other human activity coming from Hawaii represent the greatest potential for bringing invasive species into the monument.

Dianna Parker of the NOAA Marine Debris Program learned this lesson firsthand. In October 2014, she and colleague Kyle Koyanagi joined a team of divers from the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center (PIFSC) on an annual NOAA mission to Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument to remove the tons of old fishing nets that wash up on its coral reefs each year.

In the months leading up to her departure from Honolulu, Parker learned she would need something called "quarantine clothes." In essence, they were a brand-new set of clothes set aside for each time she would step on dry land in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Furthermore, these new clothes had to be sealed in plastic bags and stored in a walk-in freezer for 48 hours before she could wear them. That made for a chilly start to the day, as Parker recalled.

The quarantine clothes were part of a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service protocol for limiting both the introduction of foreign species into the monument and the spread of species between islands within it. "Something that's native to one tiny island could be alien to the next one down the chain," said Parker. The transmission could happen via a spore on your shoe or a seed stuck to your shirt.

In addition, all of the gear and equipment they were using, such as wet suits, fins, and life vests, had to be soaked in a dilute bleach solution before being used in a new location, a protocol developed by NOAA.

For the roughly month-long mission, Parker brought six full outfits to wear on the six islands the ship planned to visit. In the end, she only visited five islands and was able to turn a t-shirt from the sixth outfit into a makeshift hat to keep the hot sun at bay.

"Having to go through that level of precaution to not bring invasive species into the monument makes you realize just how delicate things are up there," reflected Parker.

Dianna Parker of the NOAA Marine Debris Program learned this lesson firsthand. In October 2014, she and colleague Kyle Koyanagi joined a team of divers from the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center (PIFSC) on an annual NOAA mission to Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument to remove the tons of old fishing nets that wash up on its coral reefs each year.

In the months leading up to her departure from Honolulu, Parker learned she would need something called "quarantine clothes." In essence, they were a brand-new set of clothes set aside for each time she would step on dry land in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Furthermore, these new clothes had to be sealed in plastic bags and stored in a walk-in freezer for 48 hours before she could wear them. That made for a chilly start to the day, as Parker recalled.

The quarantine clothes were part of a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service protocol for limiting both the introduction of foreign species into the monument and the spread of species between islands within it. "Something that's native to one tiny island could be alien to the next one down the chain," said Parker. The transmission could happen via a spore on your shoe or a seed stuck to your shirt.

In addition, all of the gear and equipment they were using, such as wet suits, fins, and life vests, had to be soaked in a dilute bleach solution before being used in a new location, a protocol developed by NOAA.

For the roughly month-long mission, Parker brought six full outfits to wear on the six islands the ship planned to visit. In the end, she only visited five islands and was able to turn a t-shirt from the sixth outfit into a makeshift hat to keep the hot sun at bay.

"Having to go through that level of precaution to not bring invasive species into the monument makes you realize just how delicate things are up there," reflected Parker.

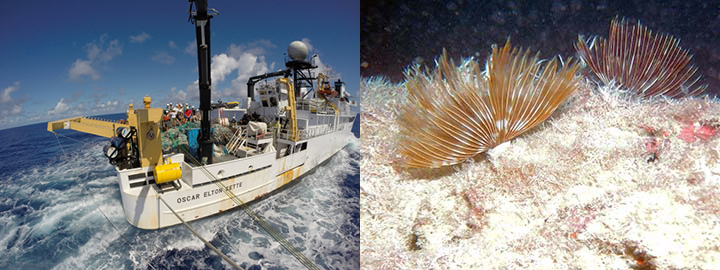

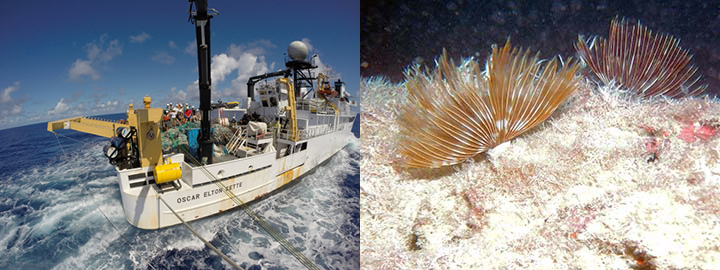

But before Parker and the rest of her team left on their mission, the vessel that would carry them, the NOAA Ship Oscar Elton Sette, first had to undergo a thorough cleaning and inspection before being granted a permit to enter the monument. The hull was scrubbed and checked by specially trained divers for even as much as a rogue barnacle. Ballast water, the water held in tanks on a ship to provide stability, was inspected closely as well because numerous creatures worldwide have been documented hitching a secret ride this way. And, of course, the ship was examined for rats, the perennial stowaways.

However, rats arrived in the monument years ago via the U.S. military activity previously based on Midway Atoll, a strategic naval base during World War II and the Cold War, and French Frigate Shoals, a runway and refueling stop for planes headed to Midway during World War II. While efforts to eradicate rats at these former military bases were successful, attempting a similar project for underwater species would be much more challenging. Marine species spread very quickly and human activities are necessarily limited by the finite amount of time we can spend underwater.

Currently, Godwin has documented about 60 non-native marine species in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, mainly at Midway, but these species—the majority of which are marine invertebrates such as tube worms and sea squirts—are not recent arrivals. Most likely harken back to the area's military days, which ended in 1994. Today the easiest way for a new marine species to get a foothold on these reefs is by colonizing "disturbed habitat," or areas humans have altered, such as seawalls or docks, as is the case at Midway and French Frigate Shoals.

"Competition with native species is pretty stiff," admits Godwin. While marine life from outside the monument can become established, they often don't have the opportunity to become invasive, he said. "But we never say never," which is why he helps train NOAA divers going to the monument to recognize the aggressive behaviors of marine invasive species.

But before Parker and the rest of her team left on their mission, the vessel that would carry them, the NOAA Ship Oscar Elton Sette, first had to undergo a thorough cleaning and inspection before being granted a permit to enter the monument. The hull was scrubbed and checked by specially trained divers for even as much as a rogue barnacle. Ballast water, the water held in tanks on a ship to provide stability, was inspected closely as well because numerous creatures worldwide have been documented hitching a secret ride this way. And, of course, the ship was examined for rats, the perennial stowaways.

However, rats arrived in the monument years ago via the U.S. military activity previously based on Midway Atoll, a strategic naval base during World War II and the Cold War, and French Frigate Shoals, a runway and refueling stop for planes headed to Midway during World War II. While efforts to eradicate rats at these former military bases were successful, attempting a similar project for underwater species would be much more challenging. Marine species spread very quickly and human activities are necessarily limited by the finite amount of time we can spend underwater.

Currently, Godwin has documented about 60 non-native marine species in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, mainly at Midway, but these species—the majority of which are marine invertebrates such as tube worms and sea squirts—are not recent arrivals. Most likely harken back to the area's military days, which ended in 1994. Today the easiest way for a new marine species to get a foothold on these reefs is by colonizing "disturbed habitat," or areas humans have altered, such as seawalls or docks, as is the case at Midway and French Frigate Shoals.

"Competition with native species is pretty stiff," admits Godwin. While marine life from outside the monument can become established, they often don't have the opportunity to become invasive, he said. "But we never say never," which is why he helps train NOAA divers going to the monument to recognize the aggressive behaviors of marine invasive species.

Godwin was on high-alert, however, when debris washed away from Japan during the 2011 tsunami began showing up in Hawaii. Most marine debris in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands comes in the form of fishing nets typically lost in the open ocean—the kind the NOAA PIFSC team was clearing from reefs. Many of the species colonizing these nets are native to the open ocean and generally do not survive in the monument’s coastal environment.

But the boats and other debris from Japan came from the coast, bringing with them the hardy and flexible marine life capable of surviving the transoceanic journey until they found another coastal home. Fortunately, Godwin found that none of the non-native Japanese species showing up on tsunami debris became established in either Hawaii or the monument.

"Marine debris is a vector [for invasive species]," said Godwin, "but we have very little control," which is why dealing with it in the monument focuses more on response than prevention. Yet with invasive species, prevention is always the goal. And when you get a glimpse of the unique place that is Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, it is not hard to understand the lengths being taken to protect it.

Godwin was on high-alert, however, when debris washed away from Japan during the 2011 tsunami began showing up in Hawaii. Most marine debris in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands comes in the form of fishing nets typically lost in the open ocean—the kind the NOAA PIFSC team was clearing from reefs. Many of the species colonizing these nets are native to the open ocean and generally do not survive in the monument’s coastal environment.

But the boats and other debris from Japan came from the coast, bringing with them the hardy and flexible marine life capable of surviving the transoceanic journey until they found another coastal home. Fortunately, Godwin found that none of the non-native Japanese species showing up on tsunami debris became established in either Hawaii or the monument.

"Marine debris is a vector [for invasive species]," said Godwin, "but we have very little control," which is why dealing with it in the monument focuses more on response than prevention. Yet with invasive species, prevention is always the goal. And when you get a glimpse of the unique place that is Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, it is not hard to understand the lengths being taken to protect it.

Packing List: Bleach, Deep Freezer, and Quarantine Clothes

Left, Dianna Parker joined a NOAA mission aboard the NOAA Ship Oscar Elton Sette to remove abandoned fishing gear that washes up in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Before the ship could enter the monument, however, it had to undergo a stringent cleaning and inspection to prevent the introduction of invasive species. Right, one example of a non-native marine species making its way into the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands is the feather duster worm Sabellastarte spectabilis. It is shown here in the harbor at Midway Atoll, Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. (NOAA)

Stowaways Not Welcome

Left, a diver conducts a marine alien species inspection of a vessel applying for an entry permit to the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. (NOAA) Top right, barnacle fouling around a sea water intake on a vessel hull. This is one of many ways potentially invasive species can hitch a ride on ships into the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. (NOAA) Bottom right, the non-native bryozoan Zoobotryon verticillatum growing on a seawall at Midway Atoll, Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Alien species like this often get a foothold in a new environment by colonizing human structures that represent “disturbed habitat.” (NOAA)

Marine Debris and Surprises from Japan

NOAA divers examining the abandoned fishing nets for potentially invasive species, as they were removing them from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands in October 2014. (NOAA)

The coral reefs of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument are the foundation of an ecosystem that hosts more than 7,000 species, including marine mammals, fishes, sea turtles, birds, and invertebrates. Many are rare, threatened, or endangered, including the endangered Hawaiian monk seal. At least one quarter are found nowhere else on Earth. (NOAA)

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument is the single largest fully protected conservation area under the U.S. flag, and one of the largest marine conservation areas in the world. It encompasses 139,797 square miles of the Pacific Ocean -- an area larger than all the country's national parks combined. (NOAA)

Last updated

Tuesday, November 8, 2022 1:40pm PST

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.