With Lobster Poacher Caught, NOAA Fishes out Illegal Traps from Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

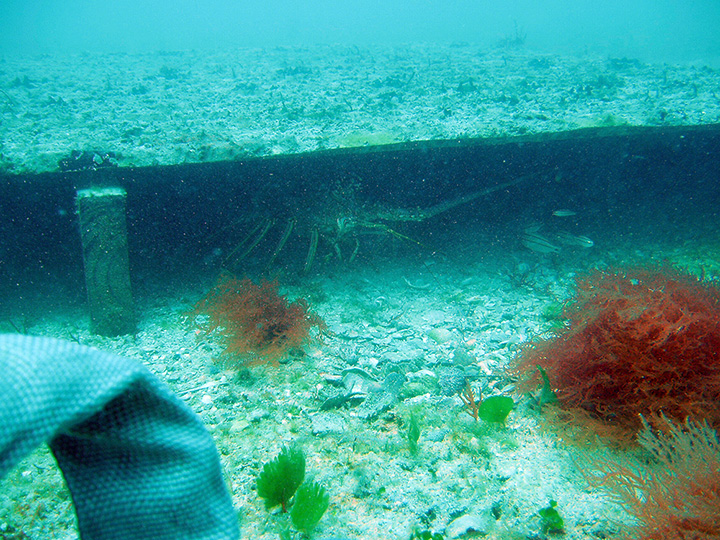

JULY 11, 2014 -- On June 26, 2014, metal sheets, cinder blocks, and pieces of lumber began rising to the ocean's surface in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. This unusual activity marked the beginning of a project to remove materials used as illegal lobster fishing devices called "casitas" from sanctuary waters. Over the course of two months, the NOAA-led restoration team plans to visit 297 locations to recover and destroy an estimated 300 casitas. NOAA's Restoration Center is leading the project with the help of two contractors, Tetra Tech and Adventure Environmental, Inc. The removal effort is part of a criminal case against a commercial diver who for years used casitas to poach spiny lobsters from sanctuary waters. An organized industry, the illegal use of casitas to catch lobsters in the Florida Keys not only impacts the commercial lobster fishery but also injures seafloor habitat and marine life. Casitas—Spanish for "little houses"—do not resemble traditional spiny lobster traps made of wooden slats and frames. "Casitas look like six-inch-high coffee tables and can be made of various materials," explains NOAA marine habitat restoration specialist Sean Meehan, who is overseeing the removal effort. The legs of the casitas can be made of treated lumber, parking blocks, or cinder blocks. Their roofs often are made of corrugated tin, plastic, quarter-inch steel, cement, dumpster walls, or other panel-like structures. Poachers place casitas on the seafloor to attract spiny lobsters to a known location, where divers can return to quite the illegal catch. "Casitas speak to the ecology and behavior of these lobsters," says Meehan. "Lobsters feed at night and look for places to hide during the day. They are gregarious and like to assemble in groups under these structures." When the lobsters are grouped under these casitas, divers can poach as many as 1,500 in one day, exceeding the daily catch limit of 250.

In addition to providing an unfair advantage to the few criminal divers using this method, the illegal use of casitas can harm the seafloor environment. A Natural Resource Damage Assessment, led by NOAA's Restoration Center in 2008, concluded that the casitas injured seagrass and hard bottom areas, where marine life such as corals and sponges made their home. The structures can smother corals, sea fans, sponges, and seagrass, as well as the habitat that supports spiny lobster, fish, and other bottom-dwelling creatures. Casitas are also considered marine debris and potentially can harm other habitats and organisms. When left on the ocean bottom, casitas can cause damage to a wider area when strong currents and storms move them across the seafloor, scraping across seagrass and smothering marine life. "We know these casitas, as they are currently being built, move during storm events and also can be moved by divers to new areas," says Meehan. However, simply removing the casitas will allow the seafloor to recover and support the many marine species in the sanctuary. There are an estimated 1,500 casitas in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary waters, only a portion of which will be removed in the current effort. In this case, a judge ordered the convicted diver to sell two of his residences to cover the cost of removing hundreds of casitas from the sanctuary.

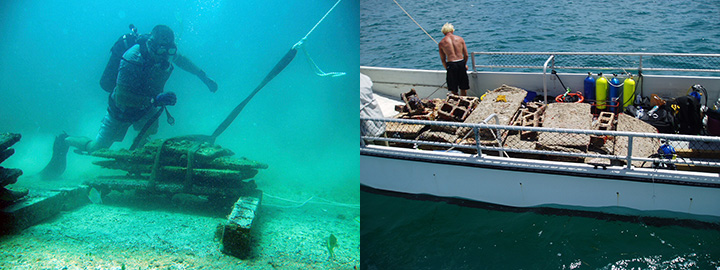

To identify the locations of the casitas, NOAA's Hydrographic Systems and Technology Program partnered with the Restoration Center and the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. In a coordinated effort, the NOAA team used Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (underwater robots) to conduct side scan sonar surveys, creating a picture of the sanctuary’s seafloor. The team also had help finding casitas from a GPS device confiscated from the convicted fisherman who placed them in the sanctuary. After the casitas have been located, divers remove them by fastening each part of a casita’s structure to a rope and pulley mechanism or an inflatable lift bag used to float the materials to the surface. Surface crews then haul them out of the water and transport them to shore where they can be recycled or disposed. For more information about the program behind this restoration effort, visit NOAA's Damage Assessment, Remediation, and Restoration Program.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.