Minds Behind OR&R: Meet Environmental Scientist Dan Hahn

By Megan Ewald, Office of Response and Restoration

This feature is part of a monthly series profiling scientists and technicians who provide exemplary contributions to the mission of NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration (OR&R). This month’s featured scientist is Dan Hahn, an environmental scientist in OR&R’s Assessment and Restoration Division.

Fishermen who become ecologists often have a kind of infectious enthusiasm, and this is certainly true of OR&R’s Dan Hahn.

Listening to Dan recount his career path, which winds from chilly Pacific shorelines to the darkest depths of the Gulf of Mexico, it’s obvious that he’s happiest on the water working to protect the marine environment. And in Dan’s case, it’s preferable if the water isn’t too cold.

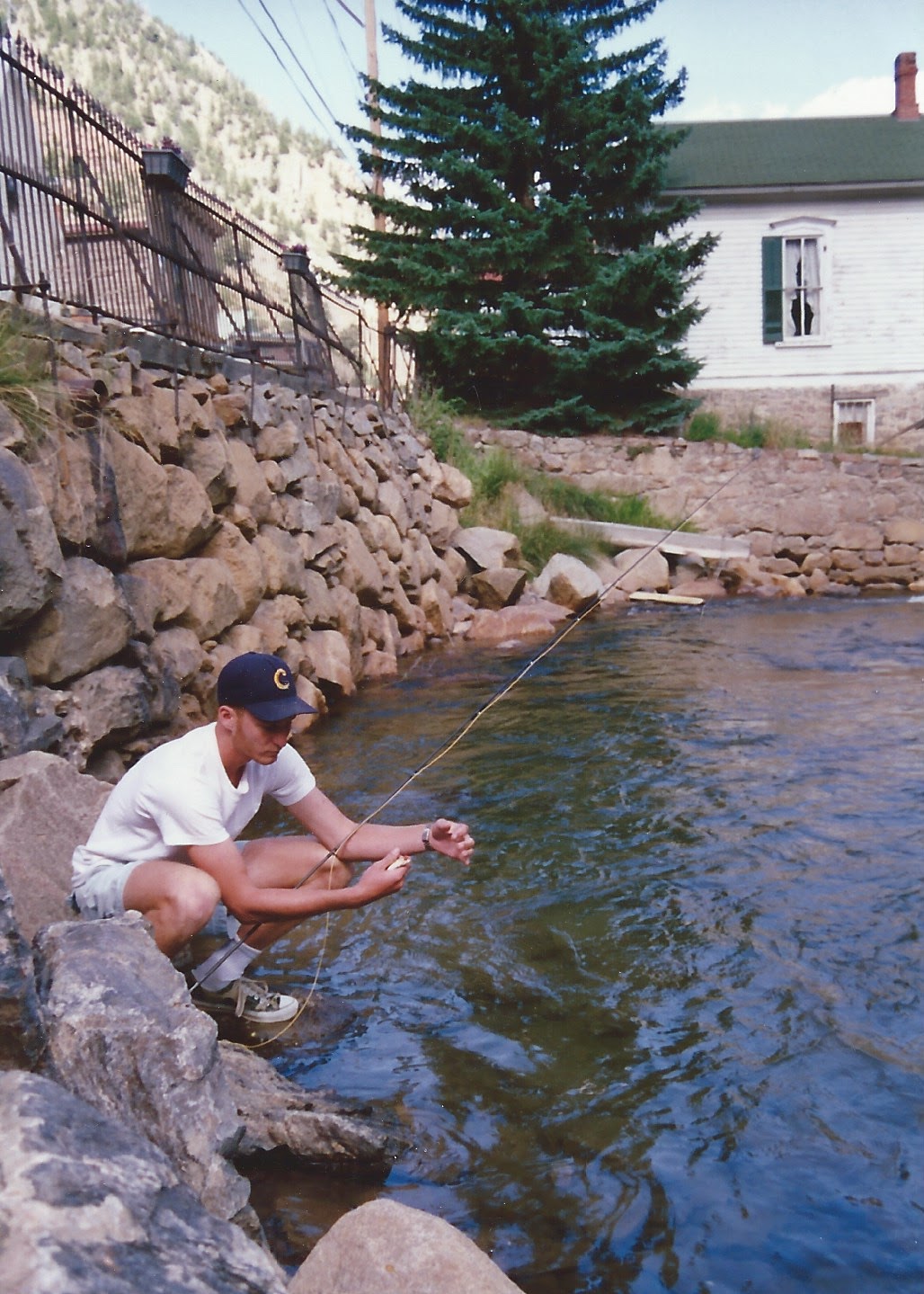

Dan grew up in Santa Rosa, California where the family spent lots of time outside hiking, bird watching, and volunteering with the Audubon Society where Dan’s father served as chapter president for a time. His mom grew up spending summers on the high mountain streams of Colorado and taught her kids to fish in the waters around Lake Tahoe.

“Some of my earliest memories of fishing are standing along the Truckee River in the early morning and crying because it was so cold,” Dan said. “But once I got a rod of my own, the crying diminished.”

Other early fishing adventures, like “poke-poling” under rocks at low tide for greenling and monkeyface prickleback, spawned out of exploring the tidepools of the rocky California coast where hermit crabs, anemones, chitons, starfish, and a myriad of other animals captured Dan’s attention. Before sixth grade, Dan went away to a summer science camp at Bodega Bay Marine Lab. Taught by world-class scientists who took the kids to explore the rocky shores and mudflats each lowtide, the camp dove deeper into the natural history of marine organisms and the complex web of connections that occurred among the plants and animals of the sea.

Coincidentally, Dan would later return to Bodega Bay while studying integrative biology at the University of California Berkeley, and even more recently for a NOAA workshop.

“So almost 30 years later, I was sleeping in the same dorm room that I had slept in during my initiation to a life of marine science,” Dan said.

While at Berkeley, Dan worked in Wayne Susa’s lab, an ecology professor who really started to shape his future direction in becoming an ecologist, and spent several months conducting field research in Panama. One of the mangrove forests where they worked abbuted on the site of a historic oil spill and the connection to Dan’s current job would only strike him years later. Dan also took a semester to study the Biology and Geomorphology of Tropical Islands, a course that took them from the fossilized reefs in Nevada to a field lab in Mo’orea, French Polynesia, where the students were literally immersed in the ecology and evolution associated with isolated tropical islands.

Graduate school took Dan to study with Shahid Naeem at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul, a place neither warm nor close to the ocean. To compensate he selected a research project studying the biological structure of Mangroves in the Florida Keys.

“I reveled at my time in the Keys, where one could actually get in the water without a wetsuit,” Dan said. “I’m happy in the heat and 100% humidity.”

In the Ecology Evolution and Behavior Program, his foundation in ecology was strengthened through the “Ecology with no apology” atmosphere that explored topics related to the influence of biodiversity on ecosystem function and the impact of biological invasions.

Dan then moved to Seattle to finish his doctorate at the University of Washington where he studied invasive seagrass that was suddenly gaining ground at the Padilla Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve and other bays in the Salish Sea and beyond. Dan spent most of the low tides, both day and night, examining the vast beds of seagrass with Avalon, a Newfoundland that doubled as research assistant and belonged to his girlfriend at the time (now spouse). While he loved studying marine ecology, the infinite ways living things interact with the world, a few years bundling up against the wind and cold of Washington State were enough. After completing his dissertation Dan decided to apply for jobs in Florida.

That’s how Dan came to OR&R’s Assessment and Restoration Division in St. Petersburg, Florida, where he’s worked for over 17 years assessing the impacts of marine pollution.

One of Dan’s first injury assessments was for an acid spill in Tampa Bay after Hurricane Frances moved across Florida from the East Coast. The spill harmed more than 135 acres of wetland habitats, including almost 80 acres of mangroves.

“So often when I go into the field it’s to document horrible conditions … but seeing what our work helped restore—the fish that thrive in the Borrow Pit restoration habita—-is so rewarding,” Dan said.

In the years since, Dan’s work with ARD has taken him to Alaskas’ Aleutian Islands, where he once spent a New Year’s Eve responding to an oil spill, to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill response and waters around the Gulf of Mexico. A decade later, scientists are still working to understand the impacts of the largest marine oil spill in U.S. history.

Dan is part of a team of scientists studying the diversity and abundance of life in the dark waters of the deep-pelagic—open ocean midwaters beyond the continental shelf, from just below the surface to just above the bottom. The deep-pelagic is home to an incredible diversity of fish invertebrates, many that migrate to shallow waters at night and are important links in connecting the surface waters with the ocean depths. However, little is known about how deep-pelagic life recovers after disruptions like the Deepwater Horizon spill. This research aims to identify long-term trends in these species to guide natural resource management.

In his free time Dan enjoys fishing and exploring Florida’s coastal waters with his family. When asked about his favorite fish, Dan can provide a lengthy list of tarpon fun-facts.

“They can gulp air-allowing them to live close to shore in low oxygen environments, they put up a huge fight and are crazy fun to catch, and they’re an incredibly old species, a prehistoric-looking, tough fish!

“The little trout I caught growing up have given way to big tarpon but I am still near, on, or in the water whenever I can be,” Dan said. “Though my job keeps me at a desk too much of the time, I am lucky to be working with a great group of dedicated people in NOAA and the Gulf States to protect and restore the ocean.”

more images

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.