More Than Two Decades Later, Have Killer Whales Recovered from the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill?

MARCH 23, 2012 — Does a killer whale instinctively know how to avoid oil spilled on the surface of its watery home? At the time of the Exxon Valdez oil spill 23 years ago, scientists and oil spill experts presumed that the answer was "yes."

They thought marine mammals were "smart" enough to steer clear of spilled oil, which possibly could harm their skin and eyes or irritate their lungs with hazardous vapors.

Yet, within 24 hours of the tanker Exxon Valdez grounding on Bligh Reef, killer whales were photographed swimming through iridescent slicks of oil in Prince William Sound, Alaska. No one was quite sure then how this exposure to oil might affect the health of killer whales living there.

For most oil spills, we don’t know how well individual species were faring before oil invaded their habitats, complicating our ability to understand health impacts after a spill. This time, however, was different.

"Orcas (killer whales) have been particularly interesting because they have been so well studied and are one of the few critters for which pre-spill information was available," NOAA biologist Gary Shigenaka says of the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill, which he has worked on extensively.

The two killer whale pods unlucky enough to swim in or near Exxon Valdez oil were from two different eco-types of killer whales, known as "resident" and "transient." Eco-types differ in several aspects of morphology (shape and structure), ecology, behavior, and genetics. For example, resident whales primarily feed on fish while transient killer whales feed on marine mammals.

Since the 1989 oil spill, scientists have followed closely the killer whale populations of Southeast Alaska. They have examined both the two pods of whales exposed to the oil in Prince William Sound as well as the other resident and transient pods which were not in the oiled areas at the time. The differences are stark.

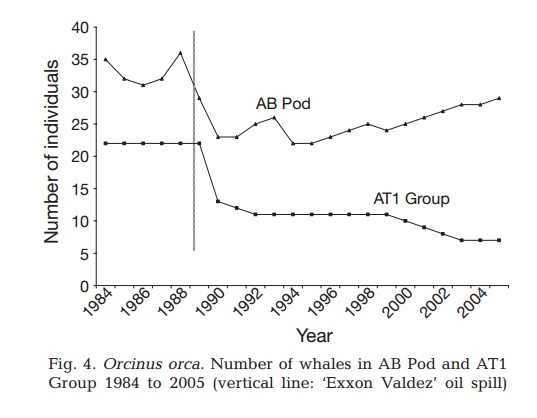

In the year and a half after the Exxon Valdez spill, both groups of killer whales swimming through Prince William Sound at the time experienced an unprecedented high number of deaths. The pod of resident killer whales lost 33% and the pod of transients 41% of their populations, according to a 2008 study by researcher Craig Matkin [PDF]. In general, killer whales tend to have very stable populations, usually losing only very young or very old whales when they lose any.

But in this case, the pods were losing a number of immature whales and breeding females as well. Missing these key members, the populations in the oiled areas were slow to bounce back, if they bounced at all. One pod of resident killer whales still hasn't reached its pre-spill numbers, while the oil-exposed transient pod’s numbers have dropped so much that NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service has listed them as a "depleted stock" under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Meanwhile, the other killer whale populations in Southeast Alaska have been growing since the mid-1980s.

Still, because researchers were unable to examine either live or most of the dead whales after the spill (and thus confirm oil-related injuries), any direct link between the spill and killer whale health has been circumstantial. Even so, Shigenaka personally believes that this indirect evidence "stands the test of time."

The crux of it lies in the fact that two pods of very different killer whale groups crashed suddenly and simultaneously after only one obvious disturbance to their environment—the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

Fast forward 21 years to April 2010 in the Gulf of Mexico. Taking these lessons about killer whales and oil from the Exxon Valdez, NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration quickly partnered up with the NOAA Fisheries Service to do reconnaissance during the Deepwater Horizon/BP oil spill, especially in oiled areas. Twenty-one species of marine mammals live in the Gulf, and bottlenose dolphins in particular potentially could be suffering some significant impacts from this spill.

Since February 2010 (before the oil spill), nearly 700 bottlenose dolphins and other species of cetaceans (dolphins and whales) in the Northern Gulf of Mexico have been stranded. These marine mammals are experiencing what’s known as an "unusual mortality event," defined as "a stranding that is unexpected, involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population, and demands immediate response." Federal and state agencies have been investigating this large die-off and any possible connections to its overlap with the Deepwater Horizon/BP oil spill.

These investigations are ongoing and the possible role of infection in these dolphins adds a twist that leaves us with plenty of questions still to answer. Nevertheless, every piece of information we learn helps create a fuller picture of how oil spills affect marine mammals, whether we’re looking at killer whales in Prince William Sound or bottlenose dolphins in the Gulf of Mexico.

For more information on killer whales and the Exxon Valdez oil spill, check out:

Matkin, C.O., Saulitis, E.L., Ellis, G.M., Olesiuk, P., Rice, S.D. 2008. Ongoing population-level impacts on killer whales Orcinus orca following the 'Exxon Valdez' oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 356:269-281.

Loughlin, T. R. Ed. Marine Mammals and the Exxon Valdez. Academic Press, San Diego, 1994.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.