The Earth Is Blue and We'd Like to Keep It That Way

OCTOBER 23, 2014 -- Often, you have to leave a place to gain some perspective. Sometimes, that means going all the way to outer space. When humans ventured away from this planet for the first time, we came to the stunning realization that Earth is blue. A planet covered in sea-to-shining-sea blue. And increasingly, we began to worry about protecting it. With the creation of the National Marine Sanctuaries system in 1972, a very special form of that protection began to be extended to miles of ocean in the United States. Today, that protection takes the form of 14 marine protected areas encompassing more than 170,000 square miles of marine and Great Lakes waters. Starting October 23, 2014, NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries is celebrating this simple, yet profound realization about our planet—that Earth is Blue—on their social media accounts. You can follow along on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. Each day, you'll see an array of striking photos (plus weekly videos) showing off NOAA's—and more importantly, your—National Marine Sanctuaries, in all of their glory. Share your own photos and videos from the sanctuaries with the hashtag #earthisblue and find regular updates at sanctuaries.noaa.gov/earthisblue.html. You can kick things off with this video: Marine sanctuaries are important places which help protect everything from humpback whales and lush kelp forests to deep-sea canyons and World War II shipwrecks. But sometimes the sanctuaries themselves need some extra protection and even restoration. In fact, one of the first marine sanctuaries, the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary off of southern California, was created to protect waters once imperiled by a massive oil spill which helped inspire the creation of the sanctuary system in the first place. At times NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration is called to this role when threats such as an oil spill, grounded ship, or even huge, floating dock endanger the marine sanctuaries and their incredible natural and cultural resources.

Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary

In March 2013, we worked with a variety of partners, including others in NOAA, to remove a 185-ton, 65-foot Japanese floating dock from the shores of Washington. This dock was swept out to sea from Misawa, Japan, during the 2011 tsunami and once it was sighted off the Washington coast in December 2012, our oceanographers helped model where it would wash up. Built out of plastic foam, concrete, and steel, this structure was pretty beat up by the time it ended up inside NOAA's Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary and a designated wilderness portion of Olympic National Park. A threat to the environment, visitors, and wildlife before we removed it, its foam was starting to escape to the surrounding beach and waters, where it could have been eaten by the marine sanctuary's whales, seals, birds, and fish.

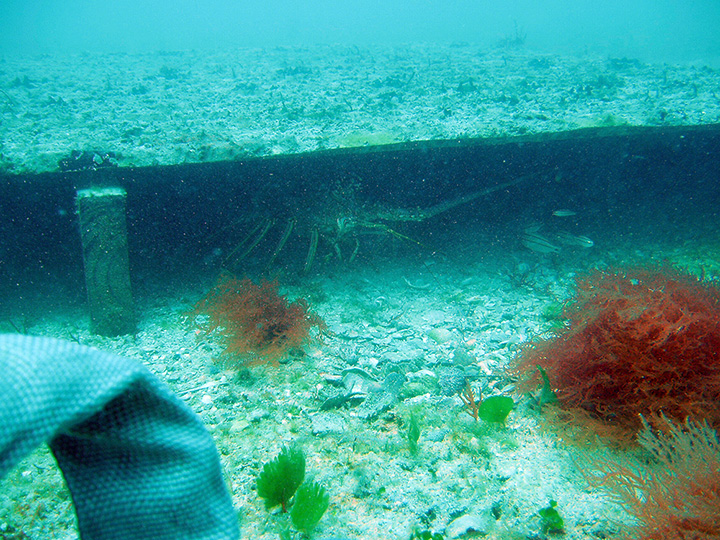

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

In an effort to protect the vibrant marine life of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, NOAA's Restoration Center began clearing away illegal lobster fishing devices known as “casitas” in June 2014. The project is funded by a criminal case against a commercial diver who for years used casitas to poach spiny lobsters from the sanctuary's seafloor. Constructed from materials such as metal sheets, cinder blocks, and lumber, these unstable structures not only allow poachers to illegally harvest huge numbers of spiny lobsters but they also damage the seafloor when shifted around during storms.

Also in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, our office and several partners ran through what it would be like to respond to an oil spill in the sanctuary waters. In April 2005, we participated in Safe Sanctuaries 2005, an oil spill training exercise that tested the capabilities of several NOAA programs, as well as the U.S. Coast Guard. The drill scenario involved a hypothetical grounding at Elbow Reef, off Key Largo, of an 800-foot cargo vessel carrying 270,000 gallons of fuel. In the scenario, the grounding injured coral reef habitat and submerged historical artifacts, and an oil spill threatened other resources. Watch a video of the activities conducted during the drill.

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument

Even hundreds of miles from the main cluster of Hawaiian islands, the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument does not escape the reach of humans. Each year roughly 50 tons of old fishing nets, plastics, and other marine debris wash up on the sensitive coral reefs of the marine monument. Each year for nearly 20 years, NOAA divers and scientists venture out there to remove the debris. This year, the NOAA Marine Debris Program’s Dianna Parker and Kyle Koyanagi are documenting the effort aboard the NOAA Ship Oscar Elton Sette. You can learn more about and keep up with this expedition on the NOAA Marine Debris Program website.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.