Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Tied to Further Impacts in Shallower Water Corals, New Study Reports

OCT. 26, 2015 — In the months and years after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, damage and poor health were found in a swath of deep-sea coral reefs and related marine life at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico. Within roughly 16 miles of the leaking wellhead, researchers discovered sickened and damaged deep-sea corals, often coated in a clumpy brown material containing petroleum, and the sediments showed evidence of out-of-balance communities of tiny invertebrates inhabiting the seafloor sediments, whose diversity took a nose dive after the spill.

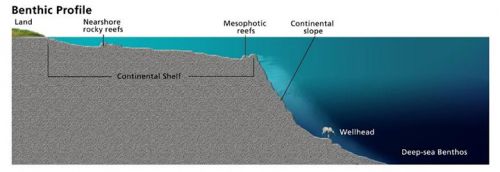

Now, a study published in October 2015 in the journal Coral Reefs reveals that this footprint of damage also extends to coral communities in shallower Gulf waters, up to 67 miles from the wellhead. In this latest study, researchers from NOAA, Florida State University, and JHT Inc. used video and images from remotely operated vehicles (ROV) to compare the health of corals on hard-bottom reefs in the "mesophotic zone" before and after the oil spill. The mesophotic zone of the ocean receives low levels of light but supports abundant fish, corals, and sponges.

The reefs in this study are important sources of habitat, food, and shelter for various marine life. These vibrant reefs also support recreational and commercial fishing for species such as snapper and grouper. Located in a region called the "Pinnacle Trend," they are at the edge of the continental shelf off Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, roughly 200–300 feet below the surface. Previous oil spill studies focused on deep-sea coral communities 4,000 feet under the ocean, located near the leaking wellhead. While the Pinnacle Trend reefs are shallower and more remote, they were below the surface oil slick that persisted for several weeks.

What Lies Beneath

Three of the largest reefs at Pinnacle Trend—bearing the colorful names Alabama Alps Reef, Roughtongue Reef, and Yellowtail Reef—were located beneath the surface slick of Deepwater Horizon oil for three to five weeks in the summer of 2010. Located between 35 and 67 miles from the leaking well, corals on the reefs were likely to have been exposed to oil and dispersant that sank from the surface down toward the seafloor. These reefs were measured against two other reef sites more than 120 miles beyond the leaking well and below the Deepwater Horizon oil slick less than three days.

Because researchers had access to ROV footage of these coral reefs dating back as far as 1989, they could directly measure what level of injury could be considered "normal" for each reef. After all, this area of the Gulf is known to be susceptible to impacts from fishing methods that contact the sea bottom. Researchers suspect that fishing was the cause of injuries observed at the two sites far from the spill because lines were wrapped around many of the coral colonies.

Not a (Sea) Fan of Damaged Corals

The three reefs closer to the wellhead had less evidence of fishing but showed major declines in health after the oil spill in 2010. More than half of the coral colonies at these sites showed signs of damage by 2011, compared with less than 10% before the spill. In comparison, the sites further from the wellhead had no significant change before and after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. In addition, injured corals the scientists noted in 2011 continued to deteriorate in the years that followed, "suggesting recovery of injured corals is unlikely," said lead author Dr. Peter Etnoyer of NOAA. Healthy corals noted after the incident in 2011 remained healthy through the end of the study in 2014, suggesting the injured corals would have been healthy but for the spill.

The researchers in this most recent study noted significant injuries among at least four species of large gorgonian octocorals (sea fans) in the three impacted reefs. Injuries took the form of overgrowth by hydroids (fuzzy marine invertebrates characteristic of unhealthy corals) and broken or bare branches of coral. To a lesser extent, corals also appeared severely discolored, with eroded polyps, had lost limbs, or toppled over entirely. An earlier study of these mesophotic reefs by some of the same scientists in the journal Deep Sea Research detected low levels of a petroleum compound known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in coral tissues and nearby seafloor sediments. The levels were low compared to sites near the wellhead, but at this point, no one yet has established what constitutes a toxic level of these compounds to marine life in mesophotic coral communities.

"The corals of the Pinnacle Trend require decades to reach maturity," said Florida State University scientist Ian MacDonald, who also contributed to the study. "Recovery will require years and it may not be immediately apparent whether the injured colonies are being replaced with new settlements. Our task is to study the process—to learn as much as we can and to ensure that nothing impedes this vital natural process."

"The results presented here may vastly underestimate the extent of impacts to mesophotic reefs in the northern Gulf of Mexico," the researchers commented, since the reefs in this study represent less than 3 percent of the mesophotic reef habitat that was known to occur beneath the oil slick. "The reefs have some prospects for recovery since many healthy colonies remain," said Etnoyer.

NOAA and its partners on this study recommend efforts to protect and restore the Pinnacles Trend reefs in order to conserve the corals and fish along this part of the ocean floor.

Learn more about the studies supported by the federal government's Natural Resource Damage Assessment for the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which determines the environmental harm due to the oil spill and response and seeks compensation from those responsible in order to restore the affected resources.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.